Also appeared at Policy Center for the New South, Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com, and Capital Finance International

The pandemic is accelerating history, in the sense that some of its recent trends are being sped up. In the case of globalization, the pandemic will not reverse it, but it will reshape it. Here we take a bird’s eye view on global trade during the pandemic, relate it to previous trends, and guess how global value chain managers and governments’ trade policymakers are likely to react.

A bird’s eye view on global trade during the pandemic

World trade had a deep dive during the first months of the global pandemic. After all, mandatory or recommended lockdowns and travel restrictions disrupted economic activities, before being scaled back in the second half of the year.

The latest WTO trade forecast pointed to a 9.2% drop in the volume of world merchandise trade in 2020, followed by a 7.2% increase in 2021. Merchandise trade is still to remain well below its previous trajectory (Figure 1).

Commercial services trade declined even more than merchandise trade, dropping 30% in the second quarter and 18% for the year to September. This is in contrast with previous global recessions when merchandise trade was at the forefront. Indeed, this crisis is different. The unusually large drop in commercial services trade is likely related to social distancing measures and travel restrictions, which curb the delivery of services that involve physical proximity to users. Less spending on services, particularly in travel-related sectors, may have also left consumers with unspent income that could be redirected toward the purchase of goods. This may partly explain the relatively small decline in merchandise trade in the first half of 2020.

Countries in all regions were impacted by the trade slump but to different degrees. Besides China as a first-in-first-out case, the fact is that trade reduction in Asia was smaller than elsewhere. Countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies in other regions helped them to sustain relatively high levels of consumption of merchandises during the crisis, with Asian countries being major producers and exporters of goods for which demand remained strong during the pandemic, including electronics and medical supplies.

Last April, we approached the “perfect storm” that COVID-19 brought to developing economies. Besides the COVID shock, they were facing other shocks from abroad (finance, remittances, tourism, and commodities). The March financial shock was partially reverted because of policies adopted by central banks in advanced and emerging market economies. Tourism went down the hill, while remittances less so.

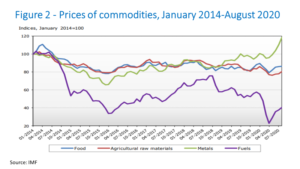

In the case of primary commodities, we had a mixed picture, with prices – other than metals – falling to different degrees in the second quarter of 2020. The price of fuels declined most, around 50% year-on-year, and they have partially recovered since then. Food prices were down 3% over the same period, while prices for agricultural raw materials dropped 13%. In contrast, prices for metals rose 6% in the same quarter (Figure 2).

With the partial reopening of economies in the second half of the year, leading to higher levels of mobility and oil consumption, the price of fuel started to rise, partially recovering from the downfall in the beginning of the pandemic. Strong price increases were recorded between May and August 2020 for food (5%), agricultural raw materials (5%), metals (19%) and fuels (40%).

Trade and GDP partially rebounded in the third quarter of 2020 in many countries, following the relaxation of social distancing measures. However, trade growth is expected to slow in the fourth quarter and beyond, as new waves of contamination have led to a partial return to – or maintenance of – confinement measures or behavior choice. The race between vaccines and COVID-19 is still on.

Previous trends in global trade

What does the trade shock look like as compared to trends prior to COVID? In fact, world trade volumes have lagged GDP growth since the 2000s, a trend accentuated after the onset of the global financial crisis (look here for long-term trends by mid-2010s).

Some transitional – and therefore potentially reversible –factors behind that may be pointed out. The weak recovery of fixed investments in advanced economies after the global financial crisis (GFC) suppressed an important source of trade volume, given the higher-than-average cross-border exchanges that characterize fixed investment goods. However, some structural trends have also been at play.

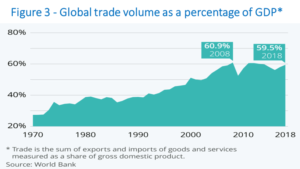

The golden era of globalization 2.0, associated with the rise of global value chains, clearly peaked by 2008. Global trade stagnated as a share of GDP and foreign direct investment fell in the 2010s (Figure 3).

The golden era reflected the combination of two major events. On the one side, trade opening measures integrated areas with cheap labor into global markets – China and others in Asia, but also Eastern Europe and Mexico. On the other, technological breakthroughs on transportation (containers, for instance) and information and communication technologies allowed a fragmentation of production processes and their geographical dispersion. The search for cost minimization could be made by spreading value chains globally and trading intermediate goods accross borders.

After steadily increasing between the mid-1980s and the mid-2000s, the trade elasticity to GDP lost height. The world’s exports-to-GDP ratio seems to have approached some plateau (or a “peak trade”). Since 2008, world trade has been rising slower than GDP at around 0.8:1, leading to a slight fall in the share of exports in global GDP. Even if transitional post-GFC factors were partially reversed, the presence of a long-term trajectory of trade elasticity displaying a slowdown already prior to the recent pattern would suggest no automatic return to the heyday.

Some structural trends can be pointed out. First, as manufacturing started to become more automated, advantages from locating production where workers were cheapest started to shrink in some of the previously disperse GVCs. This is neither a sectoral uniform nor immediate process, but overall recent technological trends point in that direction. Digitization has been sped up by COVID and tends to push additionally thereto.

In any case, the first major wave of vertical and spatial fragmentation of industrial production has completed, while services have not stepped up to the plate with the same intensity.

Furthermore, the major wave of trade-cum-structural-transformation has been followed by China’s rebalancing: going up the ladder in GVCs, while gradually lifting the domestic consumption ratio in GDP and moving toward higher GDP shares of services. As China’s middle class grew, it consumed domestically more of what it produced. Its share of world exports stopped rising in 2015, while its share of world imports continued to grow.

Advanced countries are also becoming services economies. While both the GVCs’ rise and growth-cum-structural-transformation – especially in China – were taking place, with corresponding impacts on the landscape of foreign trade, advanced economies maintained a steady evolution toward becoming services economies – a trend maintained after the GFC.

The state of current technological trajectories, as well as rising shares of services throughout would imply an anti-trade bias, given a still lower trade-propensity of services – with a few exceptions, such as tourism.

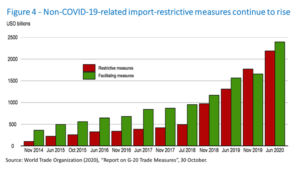

Additionally, rising trade-restrictive tax-cum-subsidy policy measures adopted in some key sectors by some countries may also have become more significant (Figure 4). In the 2010s, no major and deeper multilateral trade deals were implemented, the UK voted to leave the EU, and the US renegotiated existing trade treaties and relationships.

Globalization reshaped

The COVID-19 crisis brought an additional series of – temporary or not – trade restrictions. Many countries reacted in the early phase of the pandemic by tightening trade restrictions on exports of some medical and food products. By mid-April 2020, more than 80 countries had imposed export bans on medical devices and personal protective equipment used to curb the spread of COVID-19.

It is true that Figure 4 also shows some progress has been made in trade-facilitating measures easing restraints on international trade, as governments reckon the advantages of relying on foreign supply and demand as a complement rather than counting on self-reliance. There was also the trade pact recently agreed between members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – China, Japan, Korea, Australia, the ASEAN countries, and New Zealand. RCEP reduces tariffs on trade for goods, expands market access for some services and unifies rules of origin within the block. However, some of the distortionary barriers to trade introduced around the world over the past two years are still in place.

So, how disruptions and shortages for some essential products might affect the views of GVC managers and governments? One has watched a revival of discussions about unforeseen – or underestimated – potential costs and risks of the international fragmentation of production. On the one hand, there are voices claiming that trade dependency should be diminished, including repatriating production, as a potential way of reducing risk. On the other, such retrenchment of trade would also create substantial efficiency costs, if it goes going beyond what we described as structural factors underlying the evolution of global trade prior to the pandemic.

Supply Chain Tradeoffs: the GVC perspective

Like it happened in the Tsunami-related events earlier in the 2010s, severe supply disruptions for everything from auto parts and consumer electronics to protective equipment during the pandemic have highlighted the existence of risks from concentrating too much production and sourcing in a small number of distant low-cost locations and overreliance on just-in-time inventory management. Rising tariffs, restrictions on market access, and other manifestations of geopolitical frictions may also lead some companies to revisit their supply chains.

In some cases, there might come a view that it pays off to adopt more regional, “multilocal” sourcing and manufacturing footprints, as well as to keep higher “safety stocks” in inventory—even if these options entail somewhat higher costs.

The types of change will vary by industrial sector, as firms will have to consider a tradeoff between resilience and efficiency/costs. There is the previous trend that we alluded to in some segments toward putting production in locations closer to customers, especially when the adoption of advanced Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems is capable of offsetting higher labor costs. Medical equipment, biopharmaceutical products, semiconductors, and consumer electronics, for instance, are likely candidates to also be subject to geopolitical and government pressures. Ultimately the consequence of COVID will be a higher profile to be attributed to those considerations.

Government policies and geopolitical frictions

Governments are also likely to put greater emphasis on domestic production to reduce the risk of future supply shocks, particularly of medical supplies and equipment. Germany has expressed interest in localizing more supply chains, for example, and South Korea is exploring measures to encourage reshoring of manufacturing. This will not necessarily translate into full neglect of broader gains from globalization, but it will selectively reinforce a search for higher self-reliance. The pandemic is prompting some governments to place further controls on trade in medical and agricultural goods.

Given the revealed costs – failures – of unilateral trade policies in the style followed by President Trump in the US, they are not likely to return in President-elect Biden’s turn. But there may plurilateral efforts to broaden the agenda of trade restrictions as a quid-pro-quo in negotiations about rules and standards.

On the technology front, a potential decoupling of the US and Chinese sectors—which could make devices and IT systems in both markets no longer interoperable—might have even repercussions. China, in turn, has issued signals of a search for more self-reliance by talking about “dual circulation” and ensuring higher diversity of sources of commodity imports. Again, the COVID crisis did not create such frictions but it has given ground to an increase of their profile.

Climate Change agenda

The future of trade is also being redefined in other ways. The pandemic has had a positive spillover effect on the climate change agenda. Green recovery is the buzz word. For example, as part of its European Green Deal strategy to slash greenhouse gas emissions, the European Commission is considering pressing ahead with a proposal to impose a carbon tax on imports. This tax could redefine global competitiveness in a range of industries, particularly if accompanied by the US.

Bottom line

By intensifying geopolitical and economic forces already at work, the pandemic’s disruptive impact on international trade will leave a lasting mark. The pandemic is accelerating history, i.e. some recent trends are being sped up. The pandemic will not reverse globalization, but it will reshape it.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a visiting public policy fellow at ILAS-Columbia, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs (GWU), and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.

VIDEO – GLOBAL TRADE AND THE PANDEMIC

Click here or on the photo below https://youtu.be/Zuw6ArdcL4s

This Post Has One Comment

Pingback: Globalização remodelada pela pandemia, escreve Otaviano Canuto – Center for Macroeconomics and Development

Comments are closed.