Last December, Eric Ntumba and I were asked by the organizers of the 7th Atlantic Dialogues whether we could see spots of vulnerability to shocks in the global financial landscape, with potential systemic impacts that might evolve into another international financial crisis. Here is our map of such vulnerable spots:

ATLANTIC CURRENTS – OVERCOMING THE CHOKE POINTS, December 2018

Chapter 9 – Ten Years After the International Financial Crisis: Is a New One Looming?

Otaviano Canuto and Eric Ntumba

A review of the current literature on the topic tends to broadly suggest that a new crisis is looming for a myriad of reasons, the simplest one being that we have reached the average lifespan of previously observed favorable economic cycles before they are upset by a downturn (estimated at around 10 years). This probably largely explains the focus that has been mounting on the potential next crisis subject on the eve of the 10-year anniversary of the fall of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 marking the beginning of the last global financial crisis.

But are we really on the verge of a new International Financial Crisis? One is tempted to say “Yes!” for the following reasons:

First of all, the analysis of a battery of indicators and of a number of factors currently at play suggests that we will experience a crisis in the mid-term essentially triggered by the sharp or progressive tightening of global financial conditions after years of quantitative easing led by central bankers of key developed economies in an effort to alleviate, then eradicate the effects of the last crisis by actively supporting “the recovery in growth, employment and income”[1] mostly using their money supply levers.[2]

This situation, which principal effect has been particularly low (or negative) interest rates has made easy money available for market participants leading to a boom in credit (hence the explosion of debt levels) totally disconnected from the level of savings in the economy creating imbalances, allowing malinvestments[3] and stretching assets valuations.

Figure 1: World market capitalization has exceeded the levels witnessed in 2008

As the same central bankers progressively (or abruptly) engage in monetary policy normalization, particularly the US Fed, by raising policy rates market and shrinking balance sheets,[4] participants having substantially raised their leverage thanks to the previously very accommodative credit conditions might face mounting difficulties to service their debts. So “Yes”, there might well be a financial crisis looming, and like in all previous major crises, its principal vector will revolve around market participants’ debt levels and the pace at which financial conditions will tighten in the near future. Debate is at this stage raging on its potential scale and impact but there is a rising convergence of views toward the likely occurrence of major financial shocks.

An important difference from the run-up to the 2007-09 global financial crisis stems from the fact that this time there is no high systemic exposure to leverage of commercial banks and other retail financial intermediaries. Furthermore, stretched valuation of stocks may well be followed by portfolio corrections and correspondingly negative wealth effects but not necessarily bankruptcies. The major danger this time lies on the debt leverage of corporates, as the quality of lending – as measured by average ratings – clearly declined as standards lowered along the long period of abnormally low interest rates. At the end of the day, that’s where it will answered whether a recession – rather than a financial crisis – will be the outcome of the monetary policy normalization.

If we agree that we are on the verge of a negative financial shock and, maybe, a new Financial Crisis, how sure are we of its international nature?

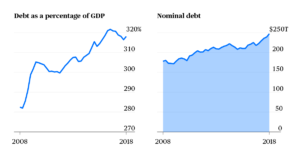

An historical review of the past financial crisis clearly makes a distinction between the ones having had a tremendous global impact like the great depression in 1929 or the “Great recession” in 2008 and the others that range from simple market corrections followed by swift recoveries or regional crisis in emerging markets (Latin America, Asia) with minor to medium effects on a couple of developed ones having exposures on them. There is a this stage a strong debate not on the potential occurrence of major shocks or crisis ahead but on the magnitude of its scale. As previously stated, the next crisis main driver will likely be the tightening of global financial conditions coupled with the current level of debts of market participants. A look at the description of these actors may provide us with a good assessment tool of what might come next. Global debt levels have exploded not just in nominal terms but also in comparison to global GDP (clearly suggesting its unsustainability in the long run). Nonetheless, one needs to examine where balance-sheet vulnerabilities are located and what are their systemic implications.

As we mentioned, this includes Global Corporate and Sovereign Debt, to the exception of the financial sector having benefited from stronger macroeconomic and macroprudential frameworks and supervision after the 2008 crisis which have induced a tight control over the banks’ leverage levels and strict requirements on building capital and liquidity buffers making them fitter to resist to stressed scenarios. It is worth noticing that the deep interconnectedness between European banks and asset bubbles in the US has dramatically shrunk since the global financial crisis, followed by the Euro crisis.

A deeper analysis on the global players shows 4 buckets of market actors able to influence the course of things:

- US which has enjoyed strong recovery and is now reaping the full benefits of its accommodative monetary policy in terms of growth, employment, and income levels while trying to keep inflation under control and keep the current momentum going by progressively normalizing its monetary policy via regular interest rate hikes. It is worth remarking, however, that the extraordinary performance so far in 2018 has a lot to do with the fiscal impulse provided by President Trump’s corporate tax cuts, in a context of full employment, the fiscal consequences of which will come to haunt the US economy in the future.

- Europe that has recovered at a slower pace, especially due to disparities in economic fundamentals of the countries in the Eurozone, but that is surely doing better and is predicted to continue doing so unless critical disruptive political or trade related factors come into play. Europe will probably, when the time is right, progressively normalize its monetary policy following the path already taken by the US.

- Emerging countries (China included) which have strongly benefited as investments destinations during the time accommodative market conditions and very low (or negative) interest rates prevailed by raising the level of their Non-Resident Capital Flows and their debt (Private and Sovereign). The idiosyncrasy of the emerging markets economies pertaining to the expected crisis lies in the span and nature of their exploding debt levels (they are for a great deal dollar or foreign currency denominated, external and short term, they show a growing trend in non-financial corporate lending/Shadow banking, and a strong rise in the level of public debt which has doubled since 2008[6]), the fact that their external debt is higher than their Exports (to the exception of China)[7] coupled with low levels of foreign exchange reserves exacerbating their vulnerability to external shocks and the prevalence of policy and political uncertainties. Emerging Economies seems to be vulnerable, given the current conditions and any tightening scenario might put their growth at risk.

- On the other hand, aggregate figures for emerging markets may hide a relevant diversity of situations. China makes a case apart as a major responsible for high debt figures exhibited by emerging markets, while holding special conditions to unwind it in some smoother way as its foreign-exchange balance sheet remains favorable. Among the other emerging markets, in turn, degrees of vulnerability differ to a large extent. [8]

- Frontier and Low-Income Markets: These countries seem already in trouble after years where market participants chasing for returns made them look very attractive and fostered high yield investments that contributed to their growth levels. They display all the vulnerabilities of emerging economies at their culminating points. They are the first at risk of a flight of funds (capital portfolio reversal) that is already well engaged. They also represent the strongest balance of payment imbalances mostly due to their strong dependence on extractive industries (with no or little value addition within their economies) and their highly extrovert nature (importing most of the consumers’ goods they need). All the above being exacerbated by a poor and unreliable policy framework, poor quality of the borrowers, the level of inequalities prevailing in their economies and weak political institutions prone to instability. The global risk appetite for this market is shrinking fast as attested by the postponement of most of these countries external issuance plans and the growing recourse to the support of International Financial Institutions. In its October 2018 Global Financial Stability Report the IMF points out that “As of August 2018, over 45% of low-income countries were at high risk of, or already in, debt distress… compared with one-third in 2016 and one-quarter in 2013”.

Those 4 buckets of country cases and their diverging economic trajectories largely point a possible international dynamics along the next financial shocks/crisis: As the US and other mature economies having recovered from the effect of the past crisis stop their quantitative easing policies and push for monetary policy normalization in an effort to maintain their fundamentals they will tighten global financial conditions, particularly by raising policy rates and making it very difficult for emerging markets actor to meet external debt service requirements and further deteriorating the already noticeable distress of frontier and low-income markets. This situation mightl be exacerbated by a capital flows portfolio reversal triggered by the renewed attractiveness of US and other mature economies as investment destinations (given the rising return on safer investments they offer in the midst of progressive decline in emerging market global risk appetite). Such new international financial shock/crisis wouldl in its first stage be an Emerging Markets one and would have direct impacts on the real economy of this group of countries and the capacity of their respective governments to meet international debt obligations as they fall due or rollover short term facilities. Its international nature would be amplified as mature economies (and their Corporate or Sovereign actors) having strong exposures on the emerging ones’ start taking the hits of their successive defaults.

This outlook is likely to be exacerbated by the following non-exhaustive number of potential crises catalysts or could be mitigated if global awareness of the current, short-term and mid-term situation leads to converging efforts of global supervision, monitoring and oversight of those vulnerabilities in order to address them efficiently and shield the real economy from their adverse potential impact:

- Global converging efforts to prevent the crisis and harmonize the response in case of its occurrence is less likely to happen in nowadays “leaderless world”[9] raising the risk to see us collectively “sleepwalking into a future crisis”[10] while an historical review of previous crisis demonstrates that only a concerted global effort piloted by a strong global leadership can help us avoid or end international financial crisis as William Rhodes puts it “One of the things that is clear in all of the crises is that strong leadership is crucial”[11].

- Mounting fears of deregulation in the US mainly might reverse progress made in the post 2008 crisis era triggering a “race to the bottom”[12] approach that will exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and the global systemic risk as supported by statements from the US administration seemingly tempted to ease or undo the restrictive measures implemented as part of the Dodd-Frank regulation in order to rein in and fence commercial banks activities from speculative ones. This risk is also pregnant in the potential aftermath of the Brexit with the temptation to undo the well advanced Basel III implementation in an attempt to attract key actors based in UK on the European continent or on flip side to retain them in the UK.

- Rising global levels of Shadow Banking (lending by non-financial corporates or institutions) especially in emerging markets.[13] This growing part of the global economy have so far escaped the scope of the 2008 post crisis regulation efforts leading to rising level of lending by hedge funds, assets managers and insurers to riskier borrowers.

- Escalation of trade tensions beyond the current US-China commercial war to systemic levels can accelerate the pace of the tightening of global financial conditions and threaten growth and global financial stability by triggering a swift drop in external demand which will put an extra burden of pressure to the balance of payments of countries having high export-to-GDP ratios or closely integrated to global value chains and in doing so deepening their existing imbalances (especially for emerging countries)[14]

- A rise in political and policy uncertainties exacerbated by a correlated rise in inequalities could constitute a serious threat both at the individual country and at the global levels putting growth and stability at serious jeopardy.

- The revival of the Sovereign-Bank nexus[15], the level of cross border exposures of banks and the fact that a couple of them have gone beyond the “too-big-to-fail” threshold witnessed in 2008 could act as a serious systemic contagion factors (geographically making Banks and financial institutions of mature economies vulnerable to emerging market borrowers risk of default; and globally from the speculative sphere to the real economy).

- Other unpredicted idiosyncratic global factors (crypto-currencies, growing disintermediation by banks to the benefits of unregulated Fintechs, etc.) suddenly disrupting market conditions or country specific factors triggering a domino effects on surrounding economies

- The compounded effects of the last crisis remnants in economies still on the path to recovery with a progressive (or sudden) change in market conditions triggered by the ongoing or expected normalization of the monetary policies in mature economies.

While we agree with the classic Austrian Business Cycle Theory approach in foreseeing increasingly deteriorated asset-liability structures as a consequence of abnormally loose monetary-financial conditions, maintained for long periods, we do not associate ourselves with the proposal also associated with that school of thought: Do nothing, let the market sort itself, since otherwise unsustainable structures may survive and thereby retard the end of a crisis.

As the Austrian school of thought would suggest, this next crisis will simply come as a consequence of excessive growth in money supply or levels of liquidity (associated with artificially low interest rates) coupled with the multiplying effect of the fractional reserve system which have set the conditions for a credit-sourced boom (and its inherent chunk of malinvestments) fostering volatile and unstable imbalances between savings and investments having successfully put the economy on an unsustainable growth path that will sooner or later lead to a credit crunch (market correction) once the money supply or liquidity contracts with the end of easing policies

This was known before the 2008 crisis (and most of its predecessor) but has seemingly not triggered the necessary reaction until it was too late. Steve H Hankee, totally in-sync with this theory, points the responsibility of global apathy on the matter to Central Bankers for having refuted this mechanics over decades[16].

While not denying the unsustainability that tends to derive from the structure of incentives prevailing during too-easy-for-too-long monetary policies, as stressed by the Austrian school, we believe in the usefulness of a Keynesian approach when it comes to the relevant answer that must be brought about:[17]

A strong policy response is needed to help avoid the crisis if possible or seriously contain its magnitude and impact on the real economy. The sooner we collectively act the better it will be for all.

- In mature economies and US in particular

- US should take a more global approach in analyzing the impact of its monetary normalization policy bearing in mind the externalities it imposes on emerging economies and the potential threat this situation, if not paced well enough, represents to the global financial stability while rightfully pursuing its recovery objectives. A strong deterioration of global market conditions triggered by a blindly self-centered monetary normalization endeavor might allow its economy to reap the expected fruits in the near term but will not be sustainable and end up in affecting the US economy own fundamentals in the long run.

- The US should attempt to ease its trade tension with China in particular via a bilateral approach or using existing or renewed multilateral channels. Other mature economies can help setting-up such a forum.

- Mature economies having recovered from the last crisis should shy away from deregulation temptations and push for the inclusion of global shadow banking actors within the regulated prudential realm to avoid losing the benefits they have gained from strengthening Banks and financial actors’ balance sheets through sound capital and liquidity buffers requirements making them “healthier and more resilient to another shock”.[18] They should also pursue consistent economic and financial overseeing processes both at the macro and micro prudential levels.

- Mature economies “lenders of last resource” must stand ready to timely intervene (even if this requires bailing out Corporate or Sovereign actors) to ring-fence any financial distress and avoid its systemic propagation. The same “ready to act” posture is strongly encouraged from International Financial Institutions.

- Drive the global convergence agenda and efforts of the 4 diverging buckets of countries (US, Europe and other mature markets, emerging markets and frontier ones) to avoid furthering the dislocation of the global economy which will only exacerbate the risks and volatility as well as empower cross-cutting contagion vectors on a global scale.

- In emerging countries

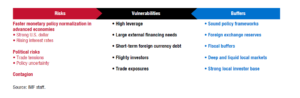

The key risks, vulnerabilities and the mitigating policy axis needed to be explored (buffers) in order to prevent the occurrence of the crisis or reduce its acuity for emerging countries are well summarized in the following diagram from the IMF:

In completion of the above, Emerging countries should:

- Strive to develop sound institutional and regulatory frameworks and strive towards more inclusive economic institutions as extractive economic ones can only bring unsustainable growth before leading to a collapse. The Institutional gap (in terms of quality) between most of these countries and the developed ones as often been named as one of the main reason they seemed trapped at the middle income level. Engaging in these reforms will not only mitigate the challenges raised by the looming crisis but also paved the way for the awaited glass ceiling breakthrough towards the club of advanced economies.

- Strive to deepen local markets and build local investors bases to foster their domestic capital levels making them more resilient to external shocks.

- Strive to fully implement Basel III recommendations and launch converging policies to address the shadow banking risks (limiting the capacity of nonbank lenders to provide credit) by regulating non-financial lending to prevent future crashes through a mix of macroeconomic and prudential frameworks.

- Strive to improve the sustainability of their public sector debts, build foreign exchange reserves, implement hedging policies and enhance their fiscal buffers.

- In low-income countries, frontier markets and Africa in particular

- Must invest time in continuously diversifying their economies, building Foreign Exchange reserves, building local investors bases and markets, putting in place “local content” policies enabling the emergence of domestic capital in order to shield away from external shocks. The diversification of the economy must no longer come as a token answer in times of trials but must be eagerly pursued, attempting to scale up to regional markets and value chains in order to support regional integration efforts.

- Must boost intra-Africa Trade and South-South partnerships in order to raise their global bargaining power and rebalance the equilibrium of forces in global trade to their own advantage. This calls for a well thought continental agenda pushing for more integration of the currently scattered African markets and a continental macroeconomic and macroprudential policy convergence drive. This can be gradually achieved through regional (or sub regional) integration initiatives building momentum until they aggregate at the continental level.

- The African Union should consider fast-tracking its 2063 agenda creating the Pan-African Financial Institutions (PAFI : the African Investment Bank, the Pan African Stock Exchange, the African Monetary Fund and the African Central Bank) as they can be of great importance in order to help regulate and oversee macroeconomics and macroprudential frameworks (hence alleviating the hazard of country specific factors) and pilot the drive to bring more economic and financial policy convergence across the continent. 2063 is just too far as a target especially for the setting-up of the African Monetary Fund and the African Investment Bank (it could remain for the single currency prospect).

- Must strive to build more inclusive and democratic institutions, able to work towards reducing the inequalities gap and foster inclusive growth to reduce country specific factors (usually political) hampering their development. They must boldly “take decisive steps toward inclusive economic institutions” to “ignite rapid economic growth”[19]

- Keep at fostering growth and market friendly regulations easing their business climate in order to raise their attractiveness levels in the eyes of foreign investors and build a conducive environment for local businesses to prosper.

Notes

[1] GFSR 2018

[2] Canuto, O. and Cavallari, M., 2017, “Bloated Central Bank Balance Sheets”, Capital Finance International, spring.

[3] In the words of Mises ““A lowering of the gross market rate of interest as brought about by credit expansion always has the effect of making some projects appear profitable which did not appear before.”

[4] Canuto, O., 2018, “Lowering the Fed balance sheet”, OMFIF Bulletin, May; Canuto, O., 2018, “The double side of the Fed’s balance sheet unwinding”, OCP Policy Center, April.

[5] 250 Trillion in Debt: the World’s Post-Lehman Legacy By Brian Chappatta September 13 in https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2018-lehman-debt/

[6] For emerging markets (excluding China) IMF GFSR October 2018.

[7] IMF suggests that emerging countries where external debt is too high relative to exports now account for 40% of aggregate GDP of emerging markets (excluding China) GFSR October 2018

[8] Canuto, O., 2018, “Emerging markets face multiple tantrums”, OCP Policy Center, July; Canuto, O., 2018, “Argentina, Turkey and the May Storm in Emerging Markets”, OCP Policy Center, June.

[9] As coined by former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown in “World economy at risk of another financial crash, says IMF”. Philip Inman, The Guardian 03 October 2018

[10] Idem

[11] IFR international Financial Review http://www.ifre.com/a-history-of-the-past-40-years-in-financial-crises/21102949.fullarticle quoting William Rhodes book “Banker to the World”.

[12] Competitive deregulation

[13] The ongoing problems with China’s P2P system as a form of “shadow banking” were anticipated sometime ago by Canuto, O. and Zhuang, L., 2015, “Shadow banking in China: a morphing target”, EconoMonitor, November.

[14] IMF GFSR October 2018

[15] Describing the transmission of risks from banks to sovereigns and vice versa (particularly acute during the Eurozone crisis where the positive relationship between bank and sovereign credit risks acted as a major threat for the stability of the Eurozone (cfr. “what drives the Sovereign Bank Nexus? By Schnabel, Isabel & Schuwer, Ulrich. 2017).

[16] The Fed’s Modus Operandi: Panic By Steve H. Hanke https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/feds-modus-operandi-panic

[17] In fact, Hyman Minsky’s Keynesian approach to finance-led business cycles and crisis shows how the Austrian school is not the only one to generate that forecast from ultra-loose, protracted abnormal liquidity. Furthermore, it can be argued that the resort to loose monetary policies in the US and other advanced economies, after the global financial crisis, might have been less intensive if fiscal policies had also been pro-actively implemented: Canuto, O., 2014, “Macroeconomics and stagnation – Keynesian-Schumpeterian wars”, Capital Finance International, spring.

[18] 250 Trillion in Debt: the World’s Post-Lehman Legacy By Brian Chappatta September 13 in https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2018-lehman-debt/

[19] “Why Nations Fail, the origins of power, prosperity and poverty” Daron Acemoglu & James A.Robinson 2012

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington D.C area, is principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development and a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank

Eric Ntumba, Atlantic Dialogues Emerging Leader and Head of Corporate, Private and Diaspora Banking, Equity Bank Limited, DRC

Watch here the debate: