Policy Center for the New South

Also: Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com, Affluent Society

The economic sanctions against Russia announced last week by the United States and Europe following the military invasion of Ukraine are having a profound impact on the Russian economy while also having repercussions at home. As in a boxing match, the expectation is that blows to the opponent can knock them out, despite the exposure on the punching side.

The United States has applied some sectoral and limited economic sanctions against Russia since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the military clashes in eastern Ukraine. Nothing comparable, however, to what was announced last week, after the entry of Russian troops into Ukraine.

Between February 22nd and 27th, starting with sanctions lifted by the United States on the secondary market for Russian sovereign debt securities issued after March 1st, as well as the German announcement to suspend certification for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, we had announcements by the United States, the 27 members of the European Union and the G7 countries of freezing assets of large Russian banks, of some Russian individuals, as well as controls on the export of technology products. Culminating with the removal of some Russian banks from the SWIFT system and banning transactions with the Central Bank of Russia.

SWIFT is a messaging network connecting banks worldwide that is considered a backbone of international finance. SWIFT is a consortium managed by employees of member banks, which include the central banks of the USA, Europe, Belgium, England, and Japan. Based in Belgium, it is a consortium linking more than 11,000 financial institutions in more than 200 countries and territories, operating as a link that makes international payments possible. To give you an idea, in 2021 the system recorded an average of 42 million messages per day, including requests and confirmations of payments, negotiations, and currency exchanges. Over 1% of these messages are believed to have involved Russian payments.

Would there be any alternatives for Russians to transfer and normalize their operations outside of SWIFT? Russia has an alternative network, the System for Transfer of Financial Messages, but it cannot be a replacement. By the end of 2020, the system only included 400 participants from 23 countries. Also, China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System could not be a perfect replacement, at least soon, as it does not incorporate SWIFT members.

Last week’s sanctions are already having a significant impact on the Russian financial system and its economy. The value of the ruble collapsed. The Central Bank of Russia was led to put interest rates up high, to limit the transmission of currency devaluation to inflation. The bank run by the population began over the weekend through ATMs. Restrictive capital controls and possibly bank holidays are ahead.

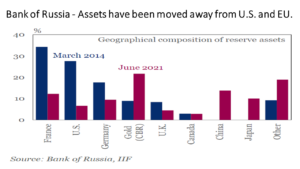

Despite the strategy of reducing exposure since the beginning of sanctions in 2014, via geographic relocation of reserves and acquisition of gold, and changing currencies in commercial transactions – a kind of “de-dollarization” – Russia has not become invulnerable and the impact will be great – Figure 1. The GDP contraction will not be light, given the tightening of financial conditions accompanying ultra-high interest rates and banks without access to foreign currency.

Figure 1

And outside Russia? Of course, the receiving side of payments – creditors, asset investors – will also be impacted. The consequences of that will only be extended if the devaluation of the corresponding assets leads to some contagion effect – for example, withdrawal of funds by investors in mutual funds forcing their managers to liquidate other assets in their portfolios to pay for the withdrawal of funds.

The sanctions were tentatively designed to minimize their effect on Russian gas imports into Europe. The sanctions announced late Saturday night were more limited in scope than the broader targeting advocated by other countries to win Germany’s support.

It will be through the rise in energy commodity prices – in addition to possible restrictions on the transport of Russian products – that the war in Ukraine will affect the economies on the other side of the fight. Also, there is a statistically proven asymmetry: what happens in the subgroup of energy commodities affects the others, such as food and metals. On top of that, the global supply of wheat supply will be negatively impacted – which is particularly impactful in some regions, such as North Africa and the Middle East. Russia is also a big supplier of fertilizers, palladium, and other products which may be affected by logistic “supply chain restrictions”.

The inflationary shock coming from higher commodity prices and likely new restrictions on supply chains will accentuate the current dilemma faced by central banks on both sides of the Atlantic, that is, how quickly and intensively to tighten financial conditions in the face of inflation that can no longer be seen as simply temporary and reversible, while seeking not to bring down the pace of economic activity or trigger financial shocks. The deteriorating macroeconomic outlook prompts analysts to predict that the Federal Reserve will not decide on a 50-basis point hike at its March meeting, opting instead for 25 basis points.

There is a fear that these economies returned to conditions like those of the early 1980s when the second oil shock occurred when inflation was already high. The bet is that Jerome Powell and his colleagues are not like Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, whose option was to bring down inflation at any cost.

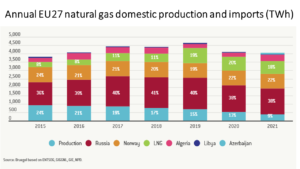

Returning to sanctions: of course, additional rounds, extending the reach of last week’s, can still be adopted in new rounds of the boxing match. The Bruegel Institute, a Brussels-based think tank, tackles scenarios of how Europe would suffer from a halt in the flow of Russian gas (Figure 2). But it would be possible.

Figure 2

The boxing match via financial and commercial sanctions has just begun. But the willingness to seek Russia’s knockout through sanctions seems more robust than the fear of its consequences.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil.