Policy Center for the New South

Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com, Capital Finance International

At the August 22-24 BRICS summit in Johannesburg, the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa said they wanted to use more of their national currencies for cross-border payments, which are currently dominated by the U.S. dollar and other global convertible currencies. Like China and the other BRICS, several other countries have also sought to develop alternative external payment mechanisms. Pairs of countries have agreed to settle commercial and financial transactions with each other in their local currencies, usually facilitated through bilateral agreements between their central banks.

Currencies across national borders fulfil three functions. First, they serve as units of account, a measure of value, for trade invoices and financial asset pricing. They also fulfill the role of a medium of exchange, that is, of settling payments as part of cross-border commercial and financial transactions. Finally, they serve to store value abroad, as public- and private-sector foreign reserves or wealth, in the form of financial or monetary assets.

We refer here to the second function, namely the settling of cross-border payments. It should be noted that, although from an individual-agent perspective the three functions may be interlinked, payment in at least a portion of transactions can be required to be made according to national public authorities’ rules.

There is an obvious reason why national governments might want to use local currencies, instead of convertible and fully usable currencies, in cross-border payments: when a country is subject to geopolitically motivated sanctions by those countries that issue the dominant international currencies and constitute destinations of external reserves in their currencies. Russia, Iran, and Venezuela are such cases in the recent past. But for geopolitical reasons, China and others are clearly also looking to reduce their vulnerability to potential sanctions against them.

Additionally, one can point to an eventual gain in terms of lower stocks of reserves in fully convertible currencies—dollar, euro, yen, sterling—necessary for central banks to ensure stability in their cross-border payments. In this case, however, it is worth noting a possible cost of bilateral cross-payment using local currencies: in bilateral relations in which a country has a systematic surplus, it tends to accumulate foreign reserves in the currency of the country on the deficit side, instead of doing so in a currency that is fully convertible and generally accepted by other agents in foreign-exchange markets.

It is enough for one side to impose the use of local currency in payments so that, even against their will, private agents of the other must accept it to make a transaction possible. Brazilian exporters, for example, now no longer face mandatory convertibility of their foreign revenues into Brazilian currency, and can dispose of their revenues in dollars or however they wish. But if the Chinese demand to pay in their currency, Brazilians will have no other option if they want to sell there.

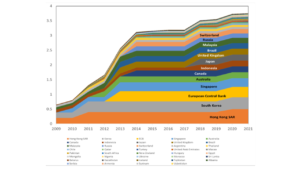

The Chinese renminbi (RMB) has seen the greatest expansion in use through bilateral external payment agreements. By the end of March 2023, the People’s Bank of China (PoBC) had signed bilateral agreements for the creation of currency swaps with central banks of 41 other countries, amounting to $480 billion and with the balance of funds activated via such lines reaching $15.6 billion (Figure 1). In addition to such credit swap lines, China has also expanded offshore clearing banks.

Figure 1: Evolution of PoBC Swap Lines (RMB trillions)

Source: Perez-Saiz and Zhang (2023).

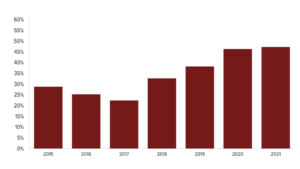

China has been able to use its currency to settle half of its foreign trade and investment transactions (Figure 2). According to an International Monetary Fund working paper, by Hector Perez-Saiz and Longmei Zhang (2023), the median use of the RMB went from zero in 2014 to 20% in 2021, based on a sample of external payments between China and 125 other countries.

Figure 2: RMB Share of China’s Total Cross-Border Settlements

Source: Hung Tran (2023).

Furthermore, the RMB has occasionally been used in bilateral transactions between third parties. Some refineries in India used RMB to buy oil from Russia. Argentina resorted in August to its bilateral line with China to pay its debt service with the IMF.

It is also worth following an ongoing project to develop digital multi-currency platform, being implemented by the central banks of China, Hong Kong, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates, with support from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Digital currencies from China and the others may become usable for external payments in a plurilateral framework.

Russia, for obvious reasons, and India have also been looking to extend the use of their currencies. Meanwhile, at a of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in May in Indonesia, members agreed to develop a framework for the settlement of external transactions in their local currencies.

The BRICS installed, in 2010, an Interbank Cooperation Mechanism to facilitate payments in local currencies by the group’s banks. In 2018, it launched BRICS Pay, a public-private partnership project for a digital payment platform in local currencies.

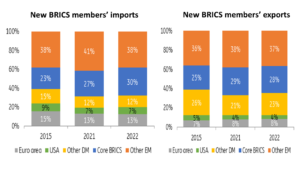

The August 22-24 BRICS summit included an invitation to six countries to join the group: Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates. Given that the original BRICS have increased their share of new members’ exports and imports (Figure 3), the use of local currencies will rise if they go along the path.

Figure 3: Core BRICS Countries Have Gained Weight in New Members’ Trade

Source: ING Economic and Financial Analysis (2023).

The growing use of local currencies in external payments will be part of what we have already called a “slow and bounded de-dollarization”. If a local currency is not fully convertible, remaining subject to regulations restricting liquidity and asset availability, as it is the case for the RMB, it will not fulfill the function of an external store of value for the bulk of agents in the global economy. Nonetheless, a partial fragmentation of the global payments system is underway.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil.