The growth and productivity performance of emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) in the last 10 years failed to repeat the achievements of the previous decade. Besides frustrating expectations that they might become the new growth pole in the global economy, their convergence to per capita incomes of advanced economies has suffered a setback. Nonetheless, the path of policies and reforms to be pursued in that direction remains the same.

Recoupling or switchover

Ten years ago, in the aftermath of the 2007-08 global financial crisis (GFC), developing economies as a whole looked – to some, like us (Canuto, 2010) – poised to not only decouple their growth from advanced economies under stress, but possibly take over the position of growth locomotive in the global economy. While the rich world would take some time before putting its post-crisis house in order, developing countries seemed to be ready even to become a force pulling them forward.

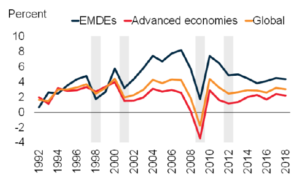

During the years before the GFC, developing economies (EMDEs) had exhibited higher and rising GDP growth rates relative to advanced economies (Chart 1). In the eve of the GFC, EMDE’s shares of the global GDP annual increases were approaching 50%.

Chart 1 – Growth

Note: EMDEs – emerging markets and developing countries

Source: Kose & Ohnsorge (2019)

GFC had originated in advanced economies and, given the crisis legacy, they were expected to undergo a period of slower growth. On the other side, the structural factors behind the EMDE’s previous growth performance might allow them not only to “decouple” from the advanced economies’ slowdown, but maybe even help pull them up. We called this as a “locomotive switchover” hypothesis.

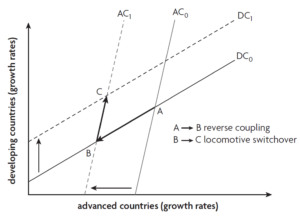

Chart 2, on the growth interdependence between the two groups of economies, provides a simplified illustration of possible outcomes. Channels for growth interdependence may be interpreted here as trade and corresponding investment prospects and as factor incomes abroad (return on foreign assets, remittances). The steepness of the lines for advanced countries (AC) reflects the pre-crisis smaller weight of developing countries (DC) in the former’s performance, whereas the greater sensitivity of DC to variations in AC growth rates is expressed in the slopes of the corresponding lines. The legacy of the crisis on AC is exemplified by the shift from AC0 to AC1. The adverse impact of slower advanced-country growth on developing countries – which we call the negative “recoupling” of developing countries—is reflected in a global move from point A to point B. However, if new “autonomous” sources of trend growth in DC can be tapped and DC0 shifts to DC1, then the global economy can settle at point C. Here, not only can developing countries escape from the negative recoupling, but there can also be a “switchover”, where developing countries become the global growth locomotives and partially rescue advanced economies.

Chart 2 – Recoupling and Switchover

Source: (Canuto, 2010)

However, since 2010, EMDEs’ growth rates have been lower than before the GFC, with a declining differential to advanced economies (chart 1). Moreover, the pace of income convergence has slowed. Here we sketch some explanation on why the transition of wagons and the locomotive switchover were lost.

Tracks along which the post-GFC switchover would take place

Most developing countries were already moving along the following tracks before the GFC, owing largely to improvements in their economic policies during the previous decade. Given that these policies enabled these countries to outperform and respond well to shocks coming from the crisis epicenter, one might expect strong incentives to keep the pace and directions of reforms that took them to that place. They could become sources of the EMDE’s “autonomous” sources of trend growth in chart 2.

Revisiting those tracks is still relevant as moving along them remains feasible and attractive today. Likewise, preconditions of policies and reforms for such still prevail.

First, public- and private-sector balance sheets in most emerging economies were relatively clean. While deleveraging was ongoing in advanced economies, many developing countries would be able to explore untapped investment opportunities – infrastructure bottlenecks being a glaring example.

The fast post-GFC recovery in many emerging markets had reflected the good shape and sustainability of their national balance sheets. Looking forward, there would be in principle a wide range of greenfield investment opportunities in developing economies—especially in infrastructure—that might benefit from higher financial leverage by both public and private sectors (Canuto & Liaplina, 2017). Healthy public and private balance sheets and existing infrastructure bottlenecks would provide room for increased investment and higher total factor productivity in many developing countries.

Second, there would be a large inventory of technologies that the developing world would be yet to acquire, adopt, and adapt (Canuto, Dutz and Reis, 2010). Thanks to breakthroughs in information and communication, transferring those technologies was becoming cheaper and safer. Furthermore, decreased transportation costs and the breakup of vertical production chains in many sectors were facilitating poorer countries’ integration into the global economy. Technological convergence and the transfer of surplus labor to more productive tradable activities would continue, despite the advanced economies’ anemic growth.

Most developing countries faced then – and still do – a technological convergence gap relative to the frontier level of knowledge in advanced economies. Unexploited latecomer advantages were a venue for local productivity improvements via technology transfer and adaptation that remained open and wide even if the advance of technology frontiers slowed down in high-income countries. Again, policy challenges would have to be faced. Absence of complementary factors such as reliable infrastructure, access to finance, and provision of formally educated labor force needed to be gradually mitigated. Furthermore, institutional factors that negatively affect the “investment climate” tend to harm investments in technology and must be addressed (Canuto, 2019a).

Third, a flipside of the emergence of new middle classes in many emerging markets was that domestic absorption (consumption and investment) in developing countries as a group might rise relative to their own production potential. Rapidly growing middle classes across the developing world would constitute a new source of demand. Provided that South-South trade linkages were reinforced one might see a new round of successful export-led growth in smaller countries.

After World War II, Europe and Japan sustained a long growth cycle through a process of technological and mass-consumption catching up with the US frontier. Whereas, from the 1990s onward, many developing economies achieved high growth facilitated by innovations in information and communication technologies, combined with globalization, but with an important role left to developed countries for absorption of their output. The time might then had come for better matching of increases in production and consumption within developing countries. That rebalancing could become a powerful tool to fasten the speed of reducing poverty and inequality.

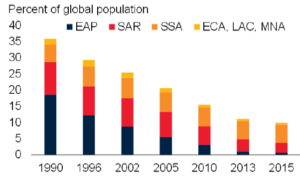

Programs of investment in infrastructure and human capital, poverty reduction, and social inclusion in developing countries would stimulate local consumption and investment, producing positive feedback loops. A higher role for effective networks of social protection and for active poverty-reduction policies in developing countries might therefore become a component of sustainable global growth. The track-record in terms of poverty reduction fed hopes in that regard (chart 3).

Chart 3 – Poverty

Note: EAP – East Asia and Pacific, SAR – South Asia, SSA – Sub-Saharan Africa, ECA – Eastern Europe and Central Asia, LAC – Latin America and the Caribbean, MNA – Middle East and North Africa.

Source: Kose & Ohnsorge (2019)

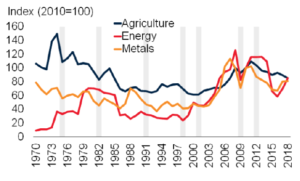

Finally, natural-resource intensive developing countries might benefit from the fact that the relative demand for commodities was expected to remain strong in the medium term, to the extent world growth after the crisis would be more dependent on developing countries as a group and demand in these countries is more commodity intensive than elsewhere. Prices would be prevented from reverting to the low levels that prevailed in the 1980’s and 1990’s (chart 4)

Once again, if appropriate governance and revenue administration mechanisms were put in place, particularly to avoid rent-seeking behavior, that natural-resource availability might be a “blessing” for those countries (Canuto & Daoulas, 2019).

Chart 4 – Commodity Prices

Source: Kose & Ohnsorge (2019)

Notwithstanding the clear visibility of those tracks, we also called attention to the comprehensive homework in terms of domestic policies and reforms that would be fundamental to be able to cross them. Some derail risks loomed ahead. And they became real.

Lost in transition

For instance, a major threat to a smooth transition to new sources of global growth was the possibility of overshooting in the inevitable asset-price adjustment accompanying the shift in relative growth prospects and perceptions of risks (Canuto, 2011). Lax monetary policies and investment slowdown in advanced economies would create a massive liquidity wave and capital flows toward EMDEs (Canuto, 2013a).

Indeed, because the creation of new assets in developing countries tended to be slower than the increase in demand for them, the price of existing assets in those markets – equities, bonds, real estate, human capital – were likely to overshoot their long-term equilibrium value. Previous history was full of examples of the negative side-effects that could arise.

Each and every one of the previous booms and busts – in Latin America, Asia, and Russia in the 1990’s, and in Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, and Ireland more recently – shared some combination of unsustainably low financial costs, asset bubbles, over-indebtedness, wage growth unwarranted by productivity gains, and domestic absorption in excess of production. In every case, these imbalances were fueled by easily identifiable periods of euphoria and sudden asset-prices increases.

True, external factors, such as foreign liquidity, were conducive – or at least permissive – to such periods of euphoria. Twin current-account and fiscal deficits (and/or currency and debt-maturity mismatches) were the rule. But our point was that powerful forces that drive up asset prices may be unleashed even without massive liquidity inflows. The scramble for available assets and a dangerous euphoria might occur through purely domestic mechanisms.

So what should developing countries do, aside from maintaining sound macroeconomic policies, curbing excessive domestic financial leverage, and attempting to isolate themselves from volatile capital inflows?

The most important task was to facilitate and strengthen the creation of new assets, and there is always much that developing countries can do in this regard. They could take advantage of moments of bonanza in available capital to build contestability, transparency, and institutional quality around markets in which greenfield investments could be implemented. They could ensure that the rules in place were consistent and favorable to funding investment projects with long maturities. And they could invest in their own capacity for project selection and design.

These and other internal reforms would serve to moderate the furious rise in the price of developing-country assets. For that reason, they would also constitute the best way to ensure that the next locomotives of global growth – and all the economies that are pulled by them – would remain on the rails.

By 2013, the over-enthusiasm with EMDEs’ growth prospects partially waned down (see chart 1). Many then believed that the broad-based growth slowdown in emerging economies was not cyclical, but a reflection of underlying structural flaws (Canuto, 2013b).

To be sure, the baseline scenario for the post-crisis “new normal” had always entailed slower global economic growth than during the pre-2008 boom. For major advanced economies, the financial crisis five years before marked the end of a prolonged period of debt-financed domestic consumption, based on wealth effects derived from unsustainable asset-price overvaluation (Canuto, 2016). The crisis had thus led to the demise of China’s export-led growth model, which had helped to buoy commodity prices and, in turn, bolster GDP growth in commodity-exporting developing countries (Canuto, 2019b).

Against this background, a return to pre-crisis growth patterns could not reasonably be expected, even after advanced economies completed the deleveraging process and repaired their balance sheets. But developing countries’ economic performance was still expected to decouple from that of developed countries and drive global output by finding new, relatively autonomous sources of growth.

It had become apparent, however, that emerging-market enthusiasts underestimated at least two critical factors. First, emerging economies’ motivation to keep the previous pace of reforms was weaker than expected. The global economic environment – characterized by massive amounts of liquidity and low interest rates stemming from unconventional monetary policy in advanced economies – led most emerging economies to use their policy space to build up existing drivers of growth, rather than moving ahead on new ones.

But the growth returns had dwindled, while imbalances had worsened. Countries like Russia, India, Brazil, South Africa, and Turkey used the space available for credit expansion to support consumption, without a corresponding increase in investment. China’s non-financial corporate debt increased dramatically, partly owing to dubious real-estate investments, as a way to avoid abrupt growth deceleration.

Moreover, nothing was done in anticipation of the end of terms-of-trade gains in resource-rich countries like Russia, Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa, which had been facing rising wage costs and supply-capacity limits. And fiscal weakness and balance-of-payments fragility became more acute in India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey.

The second problem with emerging-economy forecasts was their failure to account for the vigor with which vested interests and other political forces would resist reform – a major oversight, given how uneven these countries’ reform efforts had been prior to 2008. The inevitable time lag between reforms and results had not helped matters.

A third shortcoming of the switchover hypothesis was the underestimation of the weight of China’s growth-cum-rebalancing path across EMDEs, as well as of downward effects of the end of the super-cycle of commodity prices – metals and agricultural prices in 2011 and oil prices in 2015 (chart 4).

Fading productivity and growth engines

The growth slowdown faced by EMDEs during 2011-16 (chart 1) happened in more than 60% of EMDEs. It was deepest in Latin America and the Caribbean and mildest in South Asia. In the case of low-income countries as a group, the growth downslide was from 6.9% in 2012 to 4.8% in 2016 (Kose & Ohnsorge, 2019).

EMDEs’ investment and export growth underwent substantial declines, moving down to less than half of their rates prior to the GFC. According to Kose & Ohnsorge (2019), estimates of potential output growth in EMDEs slowed from 5.9 percent a year in 2003-07 to 4.8 percent a year in 2013-17, because of weak investment on capital stocks, demographic trends changing from dividends to liabilities, and slower productivity growth.

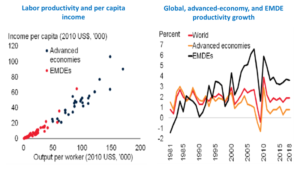

A reversal of the fast pre-GFC convergence of per capita incomes with advanced economies took place. This can be best seen by looking at productivity growth trends, as they are the primary source of lasting income growth (World Bank, 2020, ch.3). Most cross-country differences in income per capita can be associated to differences in productivity (chart 5, left side). Productivity is measured here as GDP per unit of labor, while total factor productivity (TFP) reflects the efficiency with which factor inputs are combined and is often used to proxy technological progress.

Chart 5 (right-side) shows a slowdown in productivity growth as a broad-based trend, encompassing most advanced economies and EMDEs. In advanced economies, the slowdown follows a trend that has been underway since the late 1990s (Canuto, 2014). In EMDEs, productivity growth slowed from the pre-GFC peak of 6.6% in 2007 to 3.2% in 2015, staying close to that afterward.

Productivity levels in EMDEs remain less than 20 percent of the advanced-economy average, and just 2 percent in LICs. Given such gaps as starting points, the still higher pace of productivity growth in EMDEs (chart 5, right side) is not enough to lead to a fast income convergence. According to the World Bank (2020):

“Although EMDE productivity convergence improved ahead of the global financial crisis, it is now progressing at rates that would require over a century to halve the current productivity gap with the average advanced economy. However, the pace of convergence differs across regions: more than half of EMDEs in East Asia and Pacific (EAP) are on course to halve their productivity gap in less than 40 years, while fewer than 20 percent of economies in the Middle East and North Africa (MNA), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) will likely achieve the same reduction over this timeframe.”

Chart 5 – Productivity

Source: World Bank (2020, ch.3)

The EMDE productivity slowdown reflected lower gains from labor sectoral reallocation and a slowdown in improvements in many drivers of productivity growth. Weaker investment rates and slowing TFP growth were gauged by the World Bank as equally responsible for the post-GFC productivity growth slowdown.

The very same tracks that we pointed out before as potentially leading to a continuation of the EMDE pre-GFC productivity and growth performance, eventually by sheer size switching over positions as locomotives with advanced economies, still apply: raising labor productivity economy-wide by stimulating private and public investment, and improving human capital; enhancing firm productivity, including by upgrading workforce skills; exposing firms to trade and foreign investment; facilitating the intra-sectoral reallocation of resources towards more efficient firms and a cross-sectoral diversification; and sustaining a growth-friendly macroeconomic and institutional environment.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank.

This Post Has 3 Comments

I like your article. My only recommendation would be to rely less on Kose & Ohnsorge (2019).

Best wishes Otaviano!

The article is very current for what we live, and life is getting harder.

I have made a way to have a real job at home,

without cheating, maybe it will help someone: https://bit.ly/2RbR38c

Hi. I’m glad he found cmacrodev.com website, I really like

it, the article is very useful and I shared it! In order to survive the hard times ahead we found 2 very good books, you can download them here: https://bit.ly/2RlAHdb and here: https://bit.ly/3e3Bg59

Great success with this site!

Comments are closed.