Policy Brief PB 20 – 58 – Policy Center for the New South

COVID-19 brought the global economy to a sudden stop, causing shocks to supply and demand. Starting in January 2020, country after country suffered outbreaks of the new coronavirus, with each facing epidemiological shocks that led to economic and financial shocks as a consequence.

How quickly and to what extent will national economies recover after the pandemic has passed? This will depend on success in containing the coronavirus and on exit strategies, as well as on the effectiveness of policies designed to deal with the negative economic effects of the coronavirus.

The impact of coronavirus on the global economy will extend beyond 2020. According to forecasts from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, GDP per capita at the end of 2021 is still expected to be lower than December 2019 in most countries.

Emerging markets and other developing countries, in addition to facing difficulties in dealing with their own coronavirus outbreaks, have suffered additional shocks from abroad. In their cases, the new coronavirus brought a perfect storm.

One can foresee a post-coronavirus global economy marked by higher levels of public and private debt, acceleration in digitization processes, and less globalization.

- Crisis and Recovery in the Economies Impacted by Coronavirus

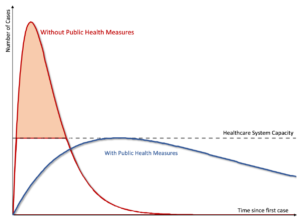

1.1 Why and how to flatten the coronavirus curves

The coronavirus crisis is primarily a public health issue, demanding containment policies that have inevitably caused shocks to economic activity. A major reason for containment is the widespread perception that, given the epidemiological dynamics of infection so far exhibited by coronavirus in most places where it has landed—and corresponding numbers of people in need of clinical care—existing local clinical care capacities tend to be swamped and death tolls are higher in a ‘do-nothing’ scenario. Therefore, policies to flatten the pandemic curve and gain time are crucial, regardless of whether or not they reduce absolute numbers of infections. Figure 1 from Gourrinchas (2020) illustrates the point. Even if it is assumed that the overall numbers of infections are the same with or without public health containment policies, lives are saved if the curve is flattened.

Figure 1: Flattening the Pandemic Curve

Source: Gourrinchas (2020).

Two major types of policies to contain or slow the spread of coronavirus have been applied. One is to identify and quarantine infected people, which has been the approach in Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea. There are two prerequisites for such an approach to be successfully implemented: there must be government capability to use technology and information to track and monitor individuals, as well as the ability to carry out widespread coronavirus testing of the population. That is not the case in most countries.

The other type of containment policy is to adopt social distancing, with various degrees of distance and government enforcement, i.e. minimizing person-to-person contact by banning travel, temporarily closing factories and schools, and official recommendations or orders for people to stay home. This horizontal approach includes some demarcation of ‘essential activities’ spared from those physical mobility restrictions. Social distancing can be used in combination with the selective focus wherever there is capacity to implement the latter.

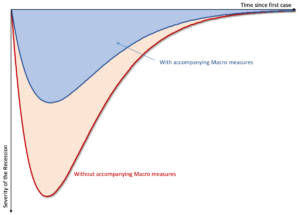

1.2 The pandemic curve generates a recession curve that also needs to be flattened

The coronavirus pandemic has led to both negative demand and supply shocks to the economy. While demand and supply would of course be negatively impacted in a ‘do-nothing’ scenario, the impact tends to be exacerbated by social-distancing policies.

The coronavirus recession has a disruptive nature that may leave scars, impeding a return to where the economy was prior to the shock. Solvent but suddenly illiquid firms may be bankrupted, unemployment is rising at a fast pace, and demand and revenues for small businesses have hastily vanished.

That is why an extraordinary role for the state as a catastrophe insurer has come to the fore, providing fiscal support—additional resources to healthcare systems, income transfers to crisis-affected people, tax relief—and credit available at favorable conditions to vulnerable firms. These emergency and temporary measures are geared to minimizing the disruptive consequences of the temporary but impactful sudden stop to the economy. Figure 2 illustrates such a flattening of the recession curve, to happen in tandem with the flattening the of pandemic curve.

Figure 2: Flattening the Recession Curve

Source: Gourrinchas (2020).

Is there a trade-off between saving lives through containment policies and output losses as a consequence of those policies? Using the historical experience of the 1918 influenza pandemic, Correia et al (2020) found that cities where non-pharmaceutical interventions took place earlier and more aggressively did not perform economically worse than other cities, and, if anything, grew faster after the pandemic was over. According to Correia et al (2020), “non-pharmaceutical interventions not only lower mortality, but also mitigate the adverse economic consequences of a pandemic”. The havoc wreaked by the pandemic dynamics in a do-nothing scenario cannot be assumed as economically stronger than the one with containment policies.

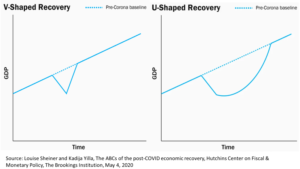

1.3 What will be the shape of the post-coronavirus economic recovery?

Data on the first-quarter 2020 GDP performance of major economies has shown how significant the impact of COVID-19 has been on economic activity and jobs, with large contractions across the board. The ongoing global recession is poised to be worse than the Great Recession after the 2008-09 global financial crisis, especially from the standpoint of emerging-market and developing economies. The depth and speed of the GDP decline will rival that of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

A post-crisis recovery is expected to begin in the second half of the year, at least in those countries where the coronavirus outbreak may be considered to have passed and policies to flatten the pandemic curve can be relaxed (Canuto, 2020c). The shocks caused by COVID-19 are profound while they last but will invariably be temporary.

Let us mention four possible stylized formats for the evolution of GDP as recoveries take hold, taken from Sheiner and Yilla (2020). The most optimistic is a V-shaped recovery (Figure 3). In this scenario, after suffering a strong blow during the pandemic, the economy soon returns to its previous trajectory. The loss of GDP during the period of restrictions—due to supply shocks and pent-up demand—is definitive. However, if there are no lasting consequences from the virus period and the corresponding economic impact on the production system and on economic agents’ conditions, everything returns to the previous normal.

Figure 3: Optimistic Curves

Less optimistic and more likely is the U shape (Figure 3). The effects of the pandemic persist, not least because the norms of social distancing remain for some time, but eventually GDP returns to its previous trajectory after a period of decline. Even if sanitary conditions are declared to be normalized, consumers and companies will hesitate before returning to their previous consumption patterns and investment plans.

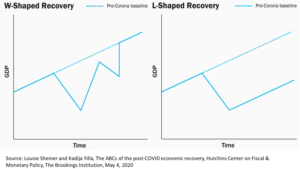

There are, however, two other more pessimistic trajectories. One is a W-shaped recovery (Figure 4). This will be the case if, after a relaxation of social-distancing policies, new COVID-19 outbreaks appear, and new rounds of these policies are implemented. This possibility is mentioned by all those who warn against any early lifting of restrictions on mobility and crowding.

Finally, there is a possibility that the damage left by the new coronavirus is permanent. In this case, the recovery takes the form of an L (Figure 4). The economy grows again, but at lower levels of GDP over time than would be the case if COVID-19 had not appeared.

Figure 4: Pessimistic Curves

Return to the pre-coronavirus GDP trajectory may be made difficult as previous investment plans can be shelved. Previously healthy companies may have gone bankrupt because of the abrupt and sudden deterioration in their operating conditions during the crisis. Changes in consumption patterns can lead to the permanent elimination of jobs without unemployed workers finding jobs quickly elsewhere. Production processes can be changed to less-efficient ways to avoid risks previously not considered relevant. The net worth of families, firms, and governments may also suffer significant deterioration during the epidemic.

Certainly, public debt is rising worldwide, something naturally expected as a result of the state’s role as the ultimate catastrophe insurer in all countries of the world. Emergency and temporary measures, financed by the public sector, have generally been adopted, aiming to minimize the disastrous consequences of the—temporary but potentially lethal—sudden stop caused by the coronavirus. Not by chance, around the world, governments have announced dramatic income transfer policies for informal workers, boosts to unemployment insurance, special lines of credit for business segments—sometimes tied to job preservation—tax relief measures and so on.

Strictly speaking, the shape of the recovery will depend on the quality—in terms of cost-effectiveness—of those public policies. On the one hand, there is the burden of public debt. On the other hand, the greater the smoothing of household income streams—especially the most vulnerable and those without accumulated savings—and the lower the wave of bankruptcy of businesses that would be healthy under normal conditions, the closer the country will be to the U shape, rather than the L.

The shape of GDP evolution will also depend on whether previous financial/fiscal fragilities and vulnerabilities are aggravated by the coronavirus-related crisis. Finally, as one may notice in the case of China, global interdependence means that what happens elsewhere also matters locally. As COVID-19 outbreaks are still unfolding in most places, it is still early to bet on any specific shape of recovery being predominant anywhere.

Obvious examples of this, in the case of developing countries, are the need to incorporate informal ‘invisible’ workers into social protection frameworks, and the urgent need to integrate slums. On the other hand, there is always a risk that underlying institutional weaknesses will be accentuated by the crisis.

- Coronavirus Has Taken Down Global Economic Giants

U.S. real GDP contracted at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 4.8% in the first quarter of 2020, the worst outcome since the last quarter of 2008. The second quarter is likely to be even worse, with forecasts pointing to a real GDP decline of around 40% SAAR. These are figures not seen since the Great Depression of the last century. More than 20 million U.S. workers lost their jobs in April 2020, and the unemployment rate reached levels as high as 14.7%.

The Eurozone is another fallen giant. In the first quarter of 2020, its GDP shrank 14.4% q/q SAAR, as lockdowns were imposed around mid-March and activity started to run at about a third below normal levels. The level of activity may have bottomed in May, assuming that restrictions will be gradually eased in the subsequent weeks. In any case, forecasts point to a 45% annualized rate of GDP drop in the first half of the year.

Japan’s real GDP is forecast to decline by more than 40% SAAR in the second quarter 2020. Daily increases in the number of infections led the government to prolong the state of emergency for an additional month after May 6.

China, in turn, suffered first an outbreak-induced sudden stop in February (Canuto, 2020a). There was a rebound in March, but not enough to allow a return to previous GDP levels, with manufacturing prospects worsening somewhat in May 2020. The normalization of domestic consumer demand and the service sector have been key drivers of China’s economic recovery in the second quarter, but demand conditions have not been very supportive. The plunge in exports in May 2020 reflects the global nature of the crisis and expresses the limits of the recovery in any single country, when a slump remains underway elsewhere. Domestically, it is worth noticing the hesitancy to consume services, even as quarantines were lifted.

The wide variation in first-quarter annual rates of GDP negative outcomes among the giants—U.S. (minus 4.9%), Eurozone (minus 14.4%), and China (minus 34.7%)—can be associated with the different timings of their COVID-19 outbreaks. But they will all have passed through a rough patch at the end of the semester.

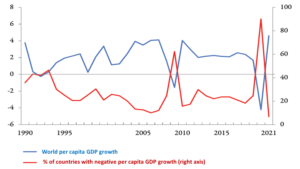

The depth and severity of the crisis were highlighted in the IMF’s World Economic Outlook forecasts released in mid-April (IMF, 2020). The IMF expected global GDP per capita to shrink by 4.2% in 2020, compared to a decline of 1.6% in 2009, during the global financial crisis (Figure 5). The vast majority (90%) of all countries are poised to exhibit negative GDP growth in 2020.

The recovery in 2021 is not expected to be enough to compensate for the ongoing GDP declines. GDP per capita in advanced economies at the end of 2021 is likely to still be lower than in December 2019. Emerging market and developing economies, in turn, face a ‘perfect storm’ and, in most cases, performance will be even gloomier (Canuto, 2020b)

Figure 5: World GDP Growth

Source: IMF (2020), World Economic Outlook, April.

- The Coronavirus Perfect Storm in Developing Countries

The global footprint of coronavirus is clear. But in developing countries, in addition to the challenges of dealing with their domestic COVID-19 outbreaks, negative shocks preceded the arrival of the virus in their territories. The perfect storm came in the wake of the decline in GDP in projections for 2020 released by the IMF in April.

3,1 Flattening coronavirus curves tends to be more difficult in developing countries

Flattening the curves of pandemic and coronavirus recession tends to be more difficult in developing countries. The flattening of the infection curve—that is, slowing down the rate of contamination and infections—is essential to avoid overloading of the clinical hospital capacity in developing countries and the death toll comes with infections. While rich countries have an average of more than four hospital beds for every thousand inhabitants, the number drops to 0.6 in low-income countries. The ability to treat critically ill patients with COVID-19 is further reduced.

Social detachment policies are also more difficult to implement when a substantial part of the population lives in slums. In turn, selective forms of isolation are difficult to implement, in the absence of technology and the public capacity to implement them, as in Singapore, South Korea, or Germany.

Measures to contain the pandemic via social/physical distancing have particularly affected the parts of the population whose income depends on their physical mobility, making it also essential to flatten the curve of the recession that accompanies the curve of the pandemic. One difficulty arises from the informality of work in developing countries, as levels of informal occupation vary from 50% to 90% of the total. Informal workers do not have benefits such as unemployment insurance, health insurance, or paid holidays. The informality of work implies that relief and recovery policies aimed at formal work, including raising unemployment insurance, reducing payroll taxes, and extending paid medical leave, are of limited scope.

Developing countries in general also do not have much fiscal space to offset the big negative shock. Their debts are more subject to exchange rate and maturity mismatches, their credit ratings are lower, and their financial markets are less deep. In addition, the ‘flight to quality’ in the financial markets that happened in February and March made it more difficult to borrow to cover public deficits.

3,2 Channels of transmission of the coronavirus crisis abroad to developing economies

Even before the new coronavirus landed on its new front—Latin America, Africa, and other regions —its economic impact had already been felt through external shocks. In addition to supply shocks derived from unavailable imports that are key to local value chains, commodity prices, tourism, and remittances have collapsed (Canuto, 2020b). Furthermore, the third dimension of the coronavirus crisis—financial shocks—have also hit developing countries.

External financial shock

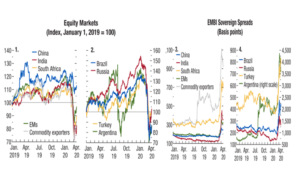

The pandemic and its economic consequences have triggered a shock to financial markets in advanced countries. Deteriorated earnings prospects and heightened uncertainty have led to a broad portfolio switch from risky assets to the safe haven of U.S. short-term Treasuries. Given the high levels of financial leverage in previous years—including among non-banking financial institutions that have become major market makers—successive margin calls have sparked massive asset fire-sales and exacerbated their dropping prices.

The Federal Reserve opened an extended and wide toolbox, establishing new channels or reinforcing existing channels to make sure that liquidity would be conveyed to all corners of the financial system. Rather than resuscitating asset prices, the aim seems to be to avoid bankruptcies and to short-circuit all the negative feedback loops and channels of contagion that otherwise would hit the real economy.

The search for safety sparked by uncertainty and fear led to a strong wave of capital outflows from emerging markets (Figure 6), and their depreciations of their currencies. According to the Institute of International Finance, foreign investors have taken $83 billion out of emerging markets since the beginning of the crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded. Concerns about debt repayment capacity and the dollar liquidity needs of some emerging markets have increased, making it more likely that the coronavirus sudden stop in advanced economies might cause a sudden stop in capital flows to emerging economies.

Poorer developing countries, in turn, have built up high and unsustainable amounts of foreign debt in the recent past (Kose et al, 2019). Servicing that debt at a time of drought in sources of refinance has become harder as commodity prices and tourism have slumped. All this is happening at a time when those countries must also face the task of flattening domestic pandemic and recession curves. The IMF and World Bank have called on governments to offer debt relief to help poorer countries deal with the coronavirus outbreak.

Figure 6: Emerging Markets: Equity Markets and Sovereign Bonds

Source: IMF (2020), World Economic Outlook, April.

Given current constraints on both liquidity and long-term financial provision by multilateral institutions posed by their balance sheets, Hausmann (2020) has floated some ideas about the use of the IMF and World Bank as vehicles for extending the reach of central bank policies in advanced economies to developing countries. For instance, U.S. Federal Reserve swap lines with central banks of other countries could be extended beyond the group with which agreements have been recently signed (Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Korea, Mexico, Norway, New Zealand, Singapore, and Sweden). Extension could be done either directly or with IMF intermediation. Another approach could be the inclusion in the quantitative easing of advanced economies’ central banks of the acquisition of less-risky emerging market bonds, which would open space for international financial institutions to focus on poorer countries.

The poorest developing countries have accumulated high and unsustainable amounts of foreign debt in the recent past. The sustainability of this debt in times of drought in terms of the sources of refinancing has become more questionable as commodity prices and tourism have fallen, as we shall see.

At their most recent meeting in April, the countries that make up the G20 agreed with the suggestion made by the IMF and the World Bank to suspend debt service of the poorest countries to official bilateral creditors, at least until the end of the year. They also suggested to private creditors that they take similar initiatives. More than ever, foreign aid will be essential so that these countries can, notwithstanding the difficulties, attempt the task of flattening their domestic pandemic and recession curves.

In addition to financial shocks, there have been declines in remittances, tourism revenues, and commodity prices (Canuto, 2020b). The combination of these shocks with the difficulties related to the flattening of domestic infection curves has configured what we call the ‘perfect storm’ for developing countries, brought by COVID-19 (Canuto, 2020c).

Remittances, foreign capital, and aid

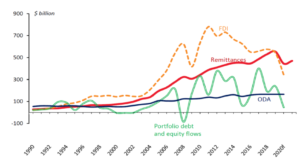

On April 22, the World Bank (2020a) published its Migration and Development Brief 32. The World Bank estimated that in 2019 there were 272 million international migrants—including 26 million refugees.

Foreign workers are often the first to lose their jobs in times of crisis, and remittance flows around the world sent by migrants to their home countries are forecast to shrink by more than US$100 billion in 2020. The global economic lockdown, which has provoked steep job losses across the world, is expected to lead to a 20% decline in remittance flows to low- and middle-income nations. That equals a fall from a record $554 billion in 2019 to US$445 billion in 2020.

Last year, remittances amounted to about 8.9% of GDP in poorer countries. For the first time, they overtook foreign direct investment (FDI) as a source of money inflows to low- and middle-income countries (Figure 7). FDI is expected to decline by even more than remittances, reflecting local recessions and the disruption of international trade. The World Bank report estimated that FDI into low- and middle-income countries could fall by more than 35%. Private portfolio flows through stock and bond markets could shrink by over 80%, while official development assistance (ODA) will maintain its steady evolution.

Figure 7: Remittances, Foreign Capital, and Aid Flows

Source: World Bank, Migration and Development Brief 32, April 2020.

Among remittance-dependent countries, vulnerable to the ongoing decline, there are fragile states including Somalia, Haiti, and South Sudan, as well as small island nations such as Tonga, with remittances accounting for more than a third of GDP in some countries. Larger countries including India, Pakistan, Egypt, Nigeria, Mexico, and the Philippines, will also be hit because remittances have become a major source of their external financing.

Migrant remittances are a fundamental source of income for poor households in many countries and the drop in flows this year will increase poverty. Remittances to Europe and central Asia are expected to fall most, crashing about 28% this year, while remittances to sub-Saharan Africa are forecast to diminish 23.1%. But all regions will face steep declines.

In the case of FDI, the latest World Investment Report by UNCTAD (2020) shows a dire picture, with the COVID-19 crisis expected to cause a deep fall. Global FDI flows are forecast to shrink by up to 40% this year, from their 2019 value of $1.54 trillion. FDI is expected to go below US$1 trillion for the first time since 2005, with an additional decline of a further 5% to 10% in 2021. A reversal to the pre-pandemic trend is expected, in an optimistic scenario, only in 2022.

International tourism receipts

On March 26, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2020) announced estimates of a decline of 20% to 30% in 2020 of international tourist arrivals, compared to 2019 figures. This would translate into a loss of international tourism receipts of between $300 billion to $450 billion, almost one third of the $1.5 trillion generated in 2019 (Figure 2). According to World Bank data, low- and middle-income countries recorded over $420 billion in international tourism receipts as exports last year, and will be heavily affected by the decline in 2020.

Figure 8: International Tourism Receipts, World (Real Change, %)

Source: UNWTO (e) estimate.

Commodity prices

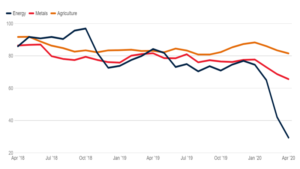

The World Bank’s (2020b) April Commodity Markets Outlook pictured how the global economic shock of the pandemic has driven most commodity prices down and is expected to result in substantially lower prices over 2020. Because of the halt in economic activities, the world’s commodity markets are likely to continue to be downbeat for months to come. Commodity-dependent emerging market and developing economies will be among the most vulnerable to the economic impacts of the pandemic.

Energy is most affected, and agriculture least. Most metal prices fell in the first quarter of 2020, reflecting the collapse in global industrial demand because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although average declines in metals prices are—for now, at least—less severe than in the global financial crisis, the sudden economic stops have taken a toll on industrial commodities such as copper and zinc, and metal prices overall are expected to fall this year. The deceleration of economic growth in China—which accounts for half of global metal demand—has weighed on industrial metal prices.

Most food commodity prices have declined in response to mitigation measures to contain the spread of COVID-19, even though part of that price decline can be attributed to the previous record production for some grains, and favorable weather conditions in key producing regions. Rice prices are the only major exception: they rose after announcements of export restrictions by some East Asian producers.

The greatest impact of the outbreak of COVID-19 has been on the crude oil market, as two-thirds of oil is used for transport. According to the World Bank report, because of travel restrictions and declining demand, crude oil demand is expected to be almost 10% lower in 2020 than in 2019. That will be more than twice as much as any previous fall (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Commodity Prices

Source: World Bank (2020), Commodity Markets Outlook, April.

Crude oil prices are forecast to average $35 a barrel in 2020, reflecting the unprecedented collapse in oil demand. Brent crude oil prices have declined 70% from their January peak. The large production cut by OPEC and other oil producers failed to lift prices in April. Natural rubber and platinum are also heavily used by the transportation industry, and their prices have tumbled.

Given the magnitude of the multiple negative shocks that COVID-19 has brought to developing countries—including domestic coronavirus infections and their recession curves, as well as external financial shocks, emigrant remittances, tourism and commodity prices—the number of people in the world living below the extreme poverty line ($1.90 per day) has been rising, a reversal of the evolution of recent times. The World Bank projects an increase of at least 49 million people below that line this year, eliminating gains made since 2017.

- Higher Debt, Deeper Digitization, and Less Globalization Will be Coronavirus Legacies

Three features of the post-pandemic global economy can already be anticipated: the worldwide rise in public and private debt levels, accelerated digitization, and a partial reversal of globalization. The first arises from the public sector’s role as the ultimate insurer against catastrophes, government policies to smooth pandemic curves, and the coronavirus recession. These will leave a legacy of massive public-sector debt worldwide. Lower tax revenues and higher social and health expenditures reflect the choice of trying to avoid widespread destruction of people’s productive and livelihood capacity during the pandemic. On the private-sector side, indebtedness will be the way to survive the sudden stop, if the result is not to be bankruptcy or closure.

The burden of meeting higher levels of public debt will be mitigated by the expected continuation of low basic interest rates in most advanced countries. However, even governments with better credit risk ratings will face debt accumulation. And sovereign debt stress is likely to increase in many other cases.

Spending cuts to contain fiscal deficits will be very costly in terms of political capital, especially after a crisis that will leave behind higher degrees of income inequality, and which is occurring after a recent period of spending restraint in many countries. Among advanced economies, the trend in recent decades has been to reduce corporate and personal income taxes. Reversing these reductions is an obvious option to fill the fiscal gap caused by the coronavirus.

Ongoing demographic trends already pointed to the need to find new ways to cover growing public spending. The coronavirus crisis will accelerate this search. However, to prevent fiscal wars between countries undermining that strategy, pluri-national consistency through tacit or explicit cooperation will be a necessary condition.

Take, for example, fiscal challenges in the Eurozone, which have been compounded by the coronavirus crisis. Highly impacted countries—including Italy and Spain—were already showing fiscal vulnerability before the virus outbreak, despite years of fiscal restrictions. The divide between countries over mutualization of debt at the Eurozone level, and the country-specific tax structures required by some—Germany—will require resolution. The announcement by the European Central Bank that it will buy another €600 billion in bonds, together with the proposal announced on May 27 by the European Commission to create a new European Union recovery fund of €750 billion to help the countries most affected by the pandemic, pushed the problem forward.

Greater intensity and frequency of stresses in the public and foreign debts of the poorest countries will also be present. The external debt of poor countries had already increased substantially since the 2008-09 global financial crisis. The G20’s postponement of the payment of its official bilateral debt this year eased the service burden in the short term, but the debt will continue to accumulate and the underlying debt trajectories will still need to be dealt with after the pandemic. A key component in this regard will be China’s role as a creditor. Its financial exposure to developing countries through credit lines and loan agreements—often linked to commercial projects at market rates and backed by guarantees—has increased in recent history.

The second result from coronavirus will be acceleration of digitization in production processes and in the provision of public services

Digitization processes taking place during the pandemic and the confinements tend to remain, to a great extent, definitively extending in areas such as education. To some extent, things like telework happening during the crisis will not reverse entirely. There will be destruction of ‘analogue’ jobs, while jobs and opportunities for entrepreneurship that require digital training will be created. Adapting the workforce to this new reality will be among the challenges highlighted by COVID-19.

A third post-coronavirus characteristic is likely to be a partial setback of productive integration across borders, which marked globalization in the decades before the global financial crisis and which has been under pressure to reverse ever since. In some cases, including medical equipment and medicines, in addition to high technology, the primacy of efficiency and cost minimization will give way to security against the risks of shocks that disrupt the availability of imports. It remains to be seen how far the demarcation lines of what will be considered ‘strategic’ by different countries will extend, in terms of the activities they need to re-shore. A key part of this issue is expected to be the intensification of the technological dispute between the United States and China (Canuto, 2019).

The coronavirus pandemic could also accentuate the ‘moving contradiction’ between a reinforcement of reorientation within countries and the need for policy coordination between countries in many areas. Dealing with challenges, including future pandemics, climate change, cyber security, terrorism, and migration, will require more multilateralism or pluri-lateralism and much less nationalism. This will mean that the lessons of coronavirus, which has encouraged national solutions, will have to be learned carefully.

- Bottom-line

COVID-19 has caused a global crisis. For the first time since the Great Depression both advanced and emerging market economies will be in recession this year. We are now in the early stages of the second phase as many countries start to ease containment policies and allow some return to economic activity. But there remains deep uncertainty about the path of the recovery.

References

Canuto, O. (2018a), Overlapping globalizations, Capital Finance International, Winter.

Canuto, O. (2018b). Can Services Replace Manufacturing as an Engine for Development? Capital Finance International, Spring.

Canuto, O. (2019). The US-China Trade War Is Accelerating China’s Rebalancing, Policy Center for the New South, November.

Canuto, O. (2020a), How Coronavirus Poses New Risks to Latin America’s Sputtering Economies, Americas Quarterly, February.

Canuto, O. (2020b), Channels of transmission of coronavirus to developing economies from abroad, Policy Center for the New South, April

Canuto, O. (2020c), More than one coronavirus curve to manage: infection, recession and external finance, Policy Center for the New South, April

Correia, S., Luck, S. & Verner, E. (2020), Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561560.

Gourrinchas, P.-O. (2020). Flatten the Curve of Infection and the Curve of Recession at the Same Time, Foreign Affairs, March.

Hausmann, R. ( 2020). Flattening the COVID-19 Curve in Developing Countries, Project Syndicate, March 24.

Horn, S., Reinhart, C. & Trebesch, C. (2019), China‘s Overseas Lending, Kiel Working Paper No. 2132, June.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2020), World Economic Outlook, April.

Khose, A. et al (2020). Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences, World Bank.

Sheiner, L. & Yilla, K. (2020), The ABCs of the post-COVID economic recovery, Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution, May

UNCTAD (2020), World Investment Report 2020, June.

UNWTO (2020), International tourist arrivals could fall by 20-30% in 2020, March.

World Bank (2020a), Migration and Development Brief 32, April.

World Bank (2020b), Commodity Markets Outlook, April.

This Post Has One Comment

Like!! Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Comments are closed.