-

There are three possible justifications for the engagement by central banks with climate change issues: financial risks, macroeconomic impacts, and mitigation/adaptation policies.

-

Regardless of the extent to which individual central banks incorporate the three prongs of motivations, they can no longer ignore climate change.

-

Last month, a BIS book referred to a “green swan” as an adaptation of the concept of a “black swan” used in finance.

Last year, extreme weather events – floods, violent storms, droughts and forest fires – associated with climate change occurred on all inhabited continents on the planet. At least 7 of them with damages estimated at more than US$ 10 billion, according to a report by Christian Aid.

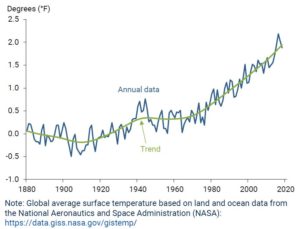

Regardless of the skepticism of some and the opinion about the responsibility of human action on the phenomenon, the proven fact is that the average global temperature at sea and on land has been rising since the 1970s, in addition to showing a greater range of variations and extremes (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Change in global average temperature relative to 1880-1900

Source: Rudebusch, G.D. Climate Change and the Federal Reserve, FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-09, March 25, 2019

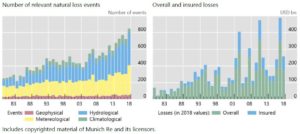

As a result of such rise in temperatures, there is a higher frequency of extreme weather events. A recently published study by Vinod Thomas and Ramón Lopez estimates that the frequency of high-intensity storms and floods could double in the next 13 years. Figure 2 depicts the worldwide increase in natural catastrophes and proportions of insured losses in the last decades:

Figure 2 – Increase in the number of extreme weather events and their insurance (1980-2018)

Source: Bolton et al, The green swan – central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change, BIS, Jan. 2020 (data from MunichRe, The Natural Disasters of 2018 in Figures)

Although with different degrees of urgency and coverage, central banks are proposing to consider climate change issues as relevant to their functions. Without the participation of the U.S. Federal Reserve, 50 central banks created the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) in December 2017, a network for mutual consultation on environmental risk management practices and those associated with climate change. Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), has stated that climate change policies will be a “crucial mission” in her mandate.

There are three possible justifications for the engagement by central banks with the topic. The first – and most obvious – is the set of risks to financial stability potentially brought about by natural disasters. This is particularly the case for financial sectors such as banks and insurance companies.

According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF) – Sustainable Finance in Focus. Climate change: a core financial stability risk, June 6, 2019 – more than US$ 2.5 trillion of global financial assets in 2016 were subject to some kind of risk derived from the impacts of climate change. As the first NGFS report noted:

“Climate-related risks are a source of financial risk and it therefore falls squarely within the mandates of central banks and supervisors to ensure the financial system is resilient to these risks.”

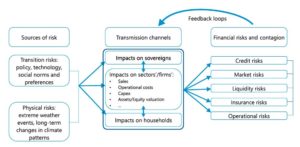

It is necessary to distinguish two types of financial risks in this context. On the one hand, there are “physical risks”, that is, threats to the value of assets resulting not only from climate shocks – the most intense and frequent extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, hurricanes and other types of storms – but also from trends like rising sea level, rising temperatures and melting polar ice caps. Such physical risks include not only potential direct losses on assets, but also their indirect impact on global value chains and repair costs.

There are also the financial risks arising from the climate change mitigation strategies that may be implemented, called “transition risks”. The move to a “low carbon economy” will change the allocation of resources, the technologies in use and the construction of infrastructure. Consequently, the strategies adopted will have consequences on the value of company assets. Just think, e.g. of the effects of “carbon taxes” or of options to accelerate the transition to renewable energy on resources and activities that would be directly impacted.

Figure 3 provides a snapshot of financial risks associated to climate change:

Figure 3 – Channels and spillovers for materialization of physical and transition risks

Source: Bolton et al, The green swan – central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change, BIS, Jan. 2020.

In passing, it is also worth noting that such risks associated with climate change also bring “opportunities”. According to estimates of growth models indicated by the IIF, a transition to a low carbon economy could eliminate climate damage equivalent to nearly 2% of the GDP of the group of G20 countries by 2050. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) suggests that what it calls a “decisive transition” could raise GDP, in the long run, by up to 2.8% on average in the G20 countries.

In addition to financial risks and stability, a second reason for central bankers’ attention to climate change concerns its impact on economic growth and inflation and, therefore, on their monetary policy decisions. ECB’s president Christine Lagarde alluded to the possibility of including impacts of climate change on the eurozone economy in the institution’s models and assessments.

The Federal Reserve officially considers climate change to be a negligible macroeconomic risk in the medium term. Nonetheless, as acknowledged by Glenn D. Rudebusch, from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, in a FRBSF Economic Letter:

“In coming decades, climate change—and efforts to limit that change and adapt to it—will have increasingly important effects on the U.S. economy. These effects and their associated risks are relevant considerations for the Federal Reserve in fulfilling its mandate for macroeconomic and financial stability.”

As well as Lael Brainard, a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System:

“Climate risks are projected to have profound effects on the U.S. economy and financial system. To fulfill our core responsibilities, it will be important for the Federal Reserve to study the implications of climate change for the economy and the financial system and to adapt our work accordingly.”

The third area of potential central bank engagement with the issue of climate change is less consensual. It is about using their balance sheets to favor its mitigation. For example, giving special treatment to “green bonds” in its asset acquisition programs, turning “quantitative easing (QE)” into a “quantitative greening”. Despite opposition from members of the ECB – such as the president of the Bundesbank, the German central bank – Christine Lagarde has referred to a role of the ECB in supporting the European Union’s economic strategy, which includes the need to mitigate climate change.

Regardless of the extent to which individual central banks incorporate the three prongs of motivations, they can no longer ignore the issue of climate change. As noted in the book “The Green Swan”, published in January by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS):

“… the growing realization that climate change is a source of financial (and price) instability: it is likely to generate physical risks related to climate damages, and transition risks related to potentially disordered mitigation strategies. Climate change therefore falls under the remit of central banks, regulators and supervisors, who are responsible for monitoring and maintaining financial stability.”

In fact, the book published by the BIS refers to a “green swan” as an adaptation of the concept of “black swan”, popularized in finance after Nassim Taleb’s 2007 book. “Black swans” refer to rare and unexpected events, with low probability, but of heavy impact and fully understandable only after they happen. By their very nature, they do not fit the analysis of normal and known conditions. “Climate change can lead to ‘green swan’ events and be the cause of the next systemic financial crisis”, note the authors of the book.

————————–

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Muito bom

Obrigado, Marina

Thanks Octaviano.Very interesting.

Comments are closed.