Karim El Aynaoui and Otaviano Canuto

This chapter was originally published in CEPR’s eBook “Scaling Up Sustainable Finance and Investment in the Global South”

Development and the changing climate will both require a substantial increase in green infrastructure investment over the next few decades in emerging market and developing countries (EMDEs). The need for investments collides with limited fiscal space in EMDEs, an obstacle that has been aggravated by the multiple shocks faced by those economies in the last few years. At the same time, those investments potentially dovetail with excess financial savings in advanced economies (AEs). In this chapter, we explore how a bridge connecting excess savings in AEs and green infrastructure investment in EMDEs might be built.

Green Infrastructure Gaps in Emerging Market and Developing Countries

The world faces a huge shortage of infrastructure investment relative to its needs. With few exceptions, such as China, this shortage is even greater in non-advanced countries.

The G20 Infrastructure Investors Dialogue estimated the volume of global infrastructure investment needed by 2040 to be $81 trillion, $53 trillion of which is needed in non-advanced countries (OECD, 2020). The Dialogue projected a gap—in other words, a shortfall in relation to the investments foreseen today—of around $15 trillion worldwide, $10 trillion of which is in non-advanced economies.

Julie Rozenberg and Marianne Fei from the World Bank have estimated that, for EMDEs to reach the Millennium Development Goals set for 2030, their infrastructure investment needs would have to correspond to 4.5% of their annual GDPs (Rozenberg and Fei, 2019). Gross spending on sustainable infrastructure in EMDEs, excluding China, corresponded to 3.5% of GDP in 2019, and needs to ramp up to 4.8% and 5.7%, respectively, in 2025 and 2030 (Bhattacharya et al, 2022).

EMDEs will be where the bulk of new physical capital is to be added in the next decades. The world population is projected to increase by 1.9 billion between 2020 and 2050, with that growth happening mostly in EMDEs other than China—especially in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. How that addition of new physical capital will be undertaken will be fundamental to success in reaching very low emissions by mid-century, building climate resilience, restoring natural capital where applicable, and accumulating human capital.

In addition to the need for infrastructure investment, there is therefore a need for its ‘greening’ as fast and as extensively as possible, in order to minimize greenhouse-gas emissions (World Bank, 2021). That requires decarbonizing the energy sector by expanding the use of renewable sources instead of coal. Increases in use-efficiency and the elimination of subsidies for the use of fossil fuels would also be part of this agenda.

Transport is now responsible for 25% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The load must be shifted to low-carbon alternatives, in addition to investments in energy-efficient equipment and support for the transition to electric vehicles and fleets.

An important part of the ‘greening’ will be in cities, involving improved water supply and sanitation services, as well as changes to energy supply, waste recycling, and greater energy efficiency through better building standards and/or renovation of existing buildings. This transition, as in the case of manufacturing and agricultural activities, will require investments in infrastructure, as well as changes to the whole chain of services.

A major obstacle to such investment is the lack of fiscal space for public spending in EMDEs, a problem made worse by the fiscal packages adopted because of the pandemic (Canuto, 2022a). The multiple, overlapping shocks faced by EMDEs in 2022 have worsened the situation (Canuto, 2022b). While the largest advanced economies can afford to increase their public debt, with a low risk of facing deteriorating financing conditions, this does not apply to most emerging economies, let alone low-income countries currently grappling with debt on unsustainable trajectories. To the greatest extent possible, domestic infrastructure investment must be ringfenced in fiscal adjustment endeavors.

Cooperation with AEs will be fundamental. These countries need to comply with their climate financing pledges made at the climate negotiations. Technology transfer will also be crucial.

Building a Bridge Between Infrastructure in EMDEs and Private Finance

Cooperation with AEs should result in bridges being built to expand the presence of private financing to infrastructure projects in EMDEs. Indeed, according to data from the Institute of International Finance (IIF), over the past 15 years, institutional investors with long time profiles in their assets, such as pension funds, have been gradually increasing their allocations to infrastructure investment and alternatives to fixed income instruments, equity, and other traditional instruments (IIF, 2021).

Stable and long-term returns from infrastructure projects dovetail well with the long-term commitments of those financial institutions, particularly in the context of excess financial wealth relative to investment opportunities in AEs—one of the factors behind declining long-term real interest rates on public and private bonds in recent decades in those economies (Canuto, 2021). Surveys carried out by the private equity database Preqin show fund managers already pointing to the decarbonization of energy as a factor in attracting private investments in infrastructure.

Abundant financial resources in world markets have been facing very low long-term real interest rates, lowered by around two percentage points over the past 30-40 years, whereas opportunities for higher returns from potential infrastructure assets are missed. The ongoing monetary-policy regime change in AEs, with rising interest rates accompanying ‘stagflation’ (Canuto, 2022b) will not erase the mismatch between relative scarcity of investment opportunities and financial savings.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, institutional investors—investment funds, insurance companies, and pension funds—in its member countries held over €180 trillion of financial assets in non-money market funds in 2017. A substantial impact on infrastructure finance might be obtained if institutional investors and other private-sector players could increase allocations to infrastructure assets. The question then becomes how to create the conditions for that to happen.

Not by chance, the ‘green revolution’ has been suggested as a trigger for a virtuous cycle of rising investment and economic growth, curbing climate change, and attending to the asset needs of financial portfolios. And, as remarked in the previous section, in the decades ahead, for demographic, climatic, and development reasons, this story must unfold increasingly on the side of EMDEs, with sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia as special cases.

The biggest challenge is to extend the bridges between, on the one hand, green infrastructure investment in non-advanced countries and, on the other, private sources of finance abundant in dollars and other convertible currencies with few opportunities to obtain returns compatible with their requirements on their liability side.

Building such a bridge requires the fulfillment of two tasks (Canuto and Liaplina, 2017). First, the development of properly structured projects, with risks and returns in line with the preferences of the different types of financial intermediation, would help to close the private financing gap in infrastructure.

Investors have different mandates and competencies regarding the management of risks associated with types of projects and phases of investment project cycles. They demand coverage of risks whose exposure is not adequately covered by market instruments. The absence of complementary instruments or investors is one of the most frequently identified reasons for failure in the financial completion of projects. Table 1 provides a snapshot of the diversity of instruments and vehicles through which private finance can participate in infrastructure projects.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Instruments and Vehicles for Infrastructure Financing

| Asset Category | Instrument |

Infrastructure Project |

Corporate Balance Sheet |

Market Vehicles-Capital Pool |

|

Fixed Income |

Bonds |

Project Bonds | Corporate Bonds, Green Bonds |

Bond indices, Bond Funds, ETFs |

| Municipal, Sub-sovereign bonds

|

||||

| Green Bonds, Sukuk | Subordinated Bonds | |||

|

Loans |

Direct/Co-Investment lending to Infrastructure project, Syndicated Project Loans |

Direct/Co-investment lending to infrastructure corporate | Debt Funds (GPs) | |

| Syndicated Loans, Securitized Loans (ABS), CLOs | Loan Indices, Loan Funds | |||

|

Mixed |

Hybrid |

Subordinated Loans/Bonds, Mezzanine Finance | Subordinated Bonds, Convertible Bonds, Preferred Stock | Mezzanine Debt Funds (GPs), Hybrid Debt Funds |

|

Equity |

Listed |

YieldCos |

Listed infrastructure & utilities stocks, Closed-end Funds, REITs, IITs, MLPs | Listed Infrastructure Equity Funds, Indices, trusts, ETFs |

|

Unlisted |

Direct/Co-investment in infrastructure project equity, PPP | Direct/Co-Investment in infrastructure corporate equity | Unlisted Infrastructure Funds |

Source: IIF (2021).

The limited fiscal space in EMDEs can be used to mainly cover such risks and enable the build-up of investment, rather than replacing private investment: crowding-in private finance instead of crowding it out. National and multilateral development banks may also favor this action instead of financing total investments.

Defining attractive investment opportunities for different types of investors and combining these perspectives more systematically around specific projects or asset pools is a promising way to fill the infrastructure financing gap. The planning and integrated issuance—with different time profiles—of fixed-income securities, bank loans, credit insurance, and others for the different moments from project preparation to operation make that combination possible.

The second task relates to the reduction in legal, regulatory, and political risks. Transparency and harmonization of rules and standards can increase the scale of comparable projects and make it possible to build project portfolios. Non-banking financial institutions often highlight the absence of ample project portfolios as a reason not to set up business lines focused on the area. This is a particularly weak point in smaller countries.

The contrast between the scarcity of investments in infrastructure—particularly in non-advanced economies—and the excess of savings invested in liquid and lower-yield assets in the global economy deserves to be confronted.

While EMDEs are grouped based on income, they are not homogeneous when it comes to the potential political risks that costly infrastructure investments in them may entail. Beyond political stability, other variables affecting investment risks are grounded in the way their public finance systems are organized. For instance, the green transition will require changes, and investments, not only at the national level, but mainly at the city and regional levels (Schoenmarker & Schramade, 2019). In turn, providing loans to subnational governments directly presents an additional risk. Higher levels of political fragmentation of subnational governments in an EMDE, for example, will negatively affect public finance management if fiscal decentralization is high. Fiscal performance incentives of subnational borrowers may also be compromised if they expect bailouts from central governments in case of a default (Rodden, 2005). Thus, it is essential that creditors and syndicates keep these variables in mind when deciding on the configuration through which investments will be injected.

Let us develop some additional points about the features of the demand- and supply-sides of infrastructure-related finance.

Demand for Infrastructure-Related Finance

In order to design effective tools to channel private investment to infrastructure projects, one needs to recognize that infrastructure investments have specific characteristics that create particular challenges for investment. They are typically long-lived assets, they usually carry low technological risk, and their operation typically occurs with high entry barriers (and hence they are usually strongly regulated assets with predictable and stable revenue streams).

Furthermore, in order to provide an overview of the available products to fund infrastructure projects, two generic categories can be identified: project and corporate finance.

Corporate finance is the traditional channel for infrastructure projects, especially private ones. Firms in charge of the infrastructure (i.e. construction and operating projects) either issue shares or borrow on capital markets to obtain the required funding. Such firms often tend to have portfolios of projects. In energy markets, utilities typically have portfolios of energy projects with different risk profiles.

Project finance is a relatively recent trend (compared to corporate finance). It builds on the idea that financing does not depend on the creditworthiness of sponsors but only on the ability of the project to repay debt and remunerate capital. In that sense, it deals with the financing of a precisely defined economic unit. Typically, because cash flows are more stable, project finance tends to allow a higher level of debt.

Table 2 shows a schematic representation of financing alternatives (see also OECD, 2015a). The main financing instruments in infrastructure projects are loans and bonds. Debt markets are the deepest markets in the world so they can be structured to form long-maturity products coherent with the long lives of infrastructure projects. Moreover, such debt instruments may benefit from the existence of players in debt markets with a preference for long-term investments. Insurance companies or pension funds tend to prefer long-maturity products to hedge their long-lived liabilities. Consequently, a large part of the project is typically financed through debt instruments (predominantly loans).

Table 2: Basic Financing Instruments

| Category

|

Instrument | Project Finance | Corporate Finance |

|

Debt |

Bonds | Project Bonds

Green Bonds |

Corporate Bonds

Green Bonds |

| Loans | Syndicated Loans

Direct Lending (to project) |

Direct Lending (to corporate)

Syndicated and Securitized Loans |

|

| Hybrid | Subordinated Debt

Mezzanine Finance |

Subordinated Bonds

Convertible Bonds |

|

|

Equity |

Listed | YieldCos | Listed Stocks, etc |

| Unlisted | Direct Investment in Project (SPV) Equity | Direct Investment in Corporate Equity |

Source: Arbouch et al (2020).

A significant part of debt instruments corresponds to ‘subordinate debt’ and, in general, instruments for both project (as mezzanine) and corporate finance that have characteristics between debt and equity (OECD, 2015). Subordinated debt can be seen as an instrument designed to absorb credit losses before senior debt. Thus, the main effect is that it increases the quality of such senior debt. In that sense, subordinated debt can be designed to have different risk/return ratios, constituting a bridge between traditional debt and equity.

Finally, equity finance may be seen as the risk capital of the project (usually required to begin the project or refinance it). Listed shares would be traded on public markets whereas unlisted shares would provide direct control over the project. Project equity finance may be placed closer to debt instruments in the sense that infrastructure contracts may impose relatively low risk/return ratios. In any case, we understand equity investment as receiving residual claims on cash flows, thus being the highest-risk investments.

Supply of Infrastructure-Related Finance

The other part of the finance ecosystem is the supply side. The role of equity in the funding of an infrastructure project has implications in terms of the finance offer.

There are two basic modes of governance for infrastructure projects, involving two different environments for the project and corresponding different roles of equity. The first mode can be organized around the infrastructure project. In general, this means that the return on the project investment will be associated exclusively with project outcomes (project finance). The second mode of governance is through a company that implements a portfolio of projects. The return on investment in these cases, from a financial point of view, depends on the risks associated with the firm’s portfolio, not just a particular project. This classification means that projects associated with project finance (typically with secured income streams) will allow the unlocking of a greater amount of debt instruments.

Equity Investors

Corporates: Corporates’ profiles may be different (as the role of equity varies) depending on whether they participate by adding the project to their balance sheet or through project finance. Traditionally, utilities have been the main corporates with interest in infrastructure. But in recent years, with the increasing importance of green infrastructure in various social and political contexts, other investors have become interested in infrastructure investment. One example is the interest from oil and gas companies in green infrastructure, such as offshore wind, energy storage, and potentially carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Institutional investors: Dedicated funds are growing in importance but are still not such a large part of the investment. Sovereign funds, infrastructure funds, insurance and pension funds, and exchange-traded funds, may be financing sources under certain conditions. However, these funds are not typically interested in exposure to relatively high risks.

Debt Investors

Commercial banks: Lending from commercial banks comes with specific constraints. Additionally, it is important to consider that Basel III, while addressing solvency problems in markets, has increased considerably the costs of lending.

Institutional investors: One finds similar institutional investors to those in equity investments. In particular, insurance and pension funds have increased their interest in infrastructure investment, as this type of asset matches well their portfolio profiles.

Governments and development banks: These institutions have been important sources of finance for infrastructure projects. Moreover, their role has consisted of providing various important functions to enhance financial conditions for infrastructure investment, including de-risking of projects, and being an early mover in risky undertakings.

Investing in global infrastructures is a risky business for institutional investors because of infrastructure-specific kinds of risks during long project life cycles. However, such long-term investments can yield real returns. This type of investment is characterized by long periods of construction of facilities. The lengthy periods of construction and the number of decades during which the facility is expected to operate is a common characteristic of infrastructure investments. Thus, payment for the produced service should be pegged to inflation. This protects the facility’s revenue stream from fluctuating price levels and ensures a predictable cash flow.

Ideally, direct private investment would be the quickest way to fill unmet infrastructure needs through public-private partnerships (PPPs). In this financing model, governments grant concessions to private entities to finance and construct infrastructure facilities. However, PPPs requires high levels of capital that very few institutional investors can allocate by themselves. They also typically entail partnering with a construction firm or other similar corporates to deliver actual physical assets. And even for institutional investors with enough assets for direct investment, evaluating the financial feasibility of infrastructure projects can be difficult, because investors generally lack the in-house expertise for this.

For smaller institutional investors with little or no experience in infrastructure, asset pooling would make more sense to increase investing capability. And by investing in such infrastructure funds, institutional investors can access unlisted infrastructure even if they lack the internal expertise or resources to assess projects unilaterally.

This type of in-house expertise can be found at the level of social entrepreneurs and small impact investors, who possess the appropriate skills to set-up and manage projects from scratch. However, given the significant difference in terms of size between social entrepreneurs and small impact investors who are highly skilled but considerably lack funding on the one hand, and institutional investors who dispose of large funding capabilities but not the required expertise to bundle different components of an infrastructure project on the other hand; a need for aggregator funds emerges, to bridge the gap between the small and the big stakeholders in the project. The main role of the aggregator funds is to address the asymmetry of information between small investors and institutional ones by identifying valuable expertise at the level of the former, which can respond to the needs of the latter (Schoenmaker & Schramade, 2019, p. 37).

A more common but even less direct manner of investing is through listed infrastructure. Becoming a shareholder of a publicly listed infrastructure company allows investors to gain exposure to the sector, while enjoying relative liquidity and committing a relatively minimal level of investment. However, a weakness of listed infrastructure products is that they tend to perform similarly to other asset classes, especially equities, as they are exposed to stock market volatility.

Risk Mitigation Measures to Attract Private-Sector Financing

Based on the ecosystem of investors described above, let us outline a map of possible functions to be performed by governments and development banks. We suggest some tools designed to de-risk infrastructure projects and mobilize private investment in infrastructure (Arbouch et al, 2021).

One way of mitigating the financial risks stemming from infrastructure projects is certainly to adopt some additional credit enhancement. Infrastructure projects, which require considerable financing amounts and present high financial risks, often need some sovereign support in the form of default guarantees. If any political changes or natural disasters compromise a project’s construction or operation, investors will need recourse in the form of such sovereign guarantees.

Government guarantees can also be essential in financing cross-border projects, such as transport infrastructure, which requires specific instruments to cover the varying risks in participating countries. Credit guarantees can also reduce the cost of borrowing by covering losses in the event of a default.

Finally, since infrastructure projects are often financed through foreign debt, special attention should be paid to mitigating currency risks through medium and long-term swap arrangements. Of course, to the greatest extent possible, more should be done to encourage finance from local investors, thus avoiding currency risks at the source.

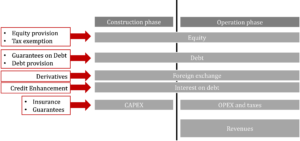

In order to map the tools that can be designed to improve investment conditions in infrastructure projects, we may think of a typical infrastructure project as made up of two phases:

- The construction phase, in which most of the costs need to be faced upfront and normally no cash flows are obtained; and

- The operation phase, in which costs are lower and income streams begin to be earned, so cash flows become increasingly positive.

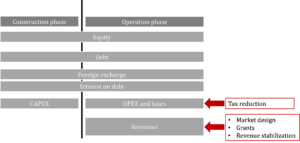

These two phases have very different risk profiles. The construction phase normally bears most risks, while the operation phase is normally exposed to less-risky cash flows. This is especially true in project-finance type investments, where expected income streams are usually agreed before construction begins for the whole life-cycle of the infrastructure.

Risks that are integral to infrastructure projects peak during the construction phase. During that phase, the private sector tends to be very reluctant to engage in a project without appropriate guarantees.

Figures 1 and 2 summarize the tools available to enhance investment conditions. In particular, Figure 1 shows possible tools associated with the construction phase, while Figure 2 depicts tools designed for the operation phase.

Figure 1: Construction Phase: Potential Financial Instruments to Mitigate Risks

Source: ‘Financing the transition to renewable energy in Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe’, EULAC Foundation.

Figure 2: Operation Phase: Revenue-Enhancing Instruments to Mitigate Risks

Source: ‘Financing the transition to renewable energy in Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe’, EULAC Foundation.

Summing Up

A bridge between private sector finance and infrastructure in EMDEs can be built if properly structured projects are developed, with risks and returns distributed in accordance with the different incentives of stakeholders. Institutional investors, like all other types of debt and equity investors, have their own incentives, constraints, and objectives when it comes to selecting countries, types of projects (greenfield vs. brownfield), and at what stage of the investment project cycle (development, construction, or operation) to invest. Inadequate coverage of risks is one of the reasons for projects often not being financial closed. Defining ‘attractive investment opportunities’ and matching investors to these opportunities in a more systematic way might make a difference.

‘Heterogeneity in the setup of projects’ is often cited as a reason why it is so difficult to push more allocations to infrastructure. Lack of data, different contractual structures, different regulatory environments—all these aspects are part of the puzzle and are addressed by different players. But also, the breadth of products tailored specifically for different types of institutional investors with their respective risk and return profiles is where greater effort can pay off. For instance, prospects for institutional investors (e.g. a pension fund) to participate at earlier stages prior to operations become more favorable when refinancing risks are covered and the construction risk is addressed.

Currency risk is a major factor faced by international investors in emerging markets. Export credit agencies can help with that challenge, although often at higher cost. Other challenges frequently named are the unavailability of financial instruments, and their respective costs and complexity in terms of difficulty of use.

Fixed-income instruments including bonds (in the context of infrastructure projects: project bonds, municipal, sub-sovereign bonds, green bonds, and sukuk), and loans (direct/co-investment lending to infrastructure project, syndicated project loans), are likely to be a better fit for the appetite of a broad range of institutional investors in EMDEs.

Development finance institutions can offer a core financial additionality by playing a key role as a catalyst, drawing private capital into long-term projects in countries and sectors where significant development results can be expected, while the market perceives high risks. Those institutions contribute their own funding (loans, equity) and/or guarantees, providing partners with an improved creditor status. Bringing partners into specific deals through syndications also generates additional financing.

Several mechanisms to mitigate and manage risks are at the disposal of the private sector. Companies can leverage financial markets to assign part of its risks to third parties through risk transfer and credit enhancement instruments. These mechanisms are currently being piloted by national and multilateral development banks. These instruments include guarantees, insurance policies, and hedging mechanisms under which, for a fee, the provider agrees to compensate the concessionaire (or its lenders) in case of default and/or loss arising from some specified circumstance. More specifically, political-risk insurance is one of the most suited mitigation tools available to curb investors’ exposure to either financial or political risks. Some sectors are more prone to regulation volatility or political pressure, where pricing for instance is more politicized. These sectors should be assessed with greater scrutiny by the infrastructure operators and require specific and customized risk mitigation mechanism (e.g., telecommunication or electricity sectors) (Müllner & Dorobantu, 2022). The financial set-up of the project can serve as an efficient lever for the private sector to mitigate risks. A diversified mix of funders, including domestic banks, international banks and multilateral banks and owners – locals and foreigners have proven to be effective in deterring political intervention and smoothing shocks. Indeed, strategic alliances with non-local entities provides another layer of hedge against political intervention, while partnering with local companies can enable an infrastructure operator to be viewed as more than just a “foreign investor” (WEF, 2015).

Institutional investors and other financial intermediaries complain about the lack of pipelines of investable projects, the scarcity of which is often highlighted as an impediment to greater commitment to infrastructure on the part of non-banking financial institutions. The labor division between public and private sectors might include an extra effort by the former to take care of basic design in cases of greater complexity and regulatory risks, where risks are harder to pre-identify and measure. The expenses of such project design can be to a great extent be reimbursed at the time concessions or other types of public-private partnership become concrete. That of course assumes public-sector planning and priority setting.

The contrast between the dearth of investment in infrastructure in EMDEs, and the savings-liquidity glut that marks the contemporaneous global economy can be reduced. Lowering legal, regulatory, and policy risks is essential. And the private sector has at its disposal a handful of tools to manage them and strike a balance between returns and risks. The availability of sophisticated, developed financial markets and instruments will help, as they facilitate partnerships between different financial agents to allow each to bear the risks that are closest to their appetites and capacities.

The burden of increasing the transparency of the legal framework and achieving political and regulatory stability falls on the public sector. High transactions costs for the private sector seeking to channel financial resources to EMDEs are ultimately borne by the public sector and taints the attractiveness of the host country. But the greater involvement of private investors and the design of economically rational financing structures will boost the funding of infrastructure investments and thereby improve the efficiency and success of infrastructure projects. Building such a bridge is within reach.

References

Arbouch, M.; Canuto, O.; and Vazquez, M. (2020). Africa’s Infrastructure Finance. T20, Task Force 3: Infrastructure Investment and Financing.

Arbouch, M.; Della Croce, R.; Canuto, O.; El Aynaoui, K.; El Jai, Y.; and Vazquez, M. (2021). Risk Mitigation Tools to Crowd in Private Investment in Green Technologies. T20, Task Force 7: Infrastructure Investment and Financing.

Bhattacharya A et al. (2022) Financing a big investment push in emerging markets and developing economies for sustainable, resilient and inclusive recovery and growth. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science, and Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Canuto, O. (2021). U.S. Bubble-Led Macroeconomics, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB-21/29, August.

Canuto, O. (2022a). “Economy Recovery and the Great Reset”, in Atlantic Currents 8th Edition: The Wider Atlantic in a Challenging Recovery, Policy Center for the New South.

Canuto, O. (2022b). Emerging economies, global inflation, and growth deceleration, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 30/22, April.

Canuto, O. and Liaplina, A. (2017). Matchmaking Finance and Infrastructure, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB-17/23, June.

IIF – Institute of International Finance (2021). Green Weekly Insight: Tackling the Infrastructure Jigsaw, June 24.

Müllner, J., Dorobantu, S. “Overcoming political risk in developing economies through non-local debt”. J Int Bus Policy (2022).

OECD (2015). Towards a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure. Public Governance and Territorial Development Directorate Public Governance Committee, September.

Rozenberg, J. and Fay, M. (2019). Beyond the Gap: How Countries Can Afford the Infrastructure They Need while Protecting the Planet. Sustainable Infrastructure; Washington, DC: World Bank.

Schoenmaker, D. and Schramade, W. (2019), “Financing environmental and energy transitions for regions and cities: creating local solutions for global challenges”, Background paper for an OECD/EC Workshop on 18 October 2019 within the workshop series “Managing environmental and energy transitions for regions and cities”, Paris.

World Bank (2021). Transitions at the Heart of the Climate Challenge, May 24.

World Economic forum “Mitigation of Political & Regulatory Risk in Infrastructure Projects Introduction and Landscape of Risk”, January 2015.